Lotte Reiniger, Ernst Lubitsch, Douglas Sirk, Wim Wenders, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder are just a handful of the best directors that Germany has produced, along with ground-breaking movements like German Expressionism and New German Cinema. Additionally, the nation has created some of the greatest horror films in cinematic history, from chilling spooky silent classics to suspenseful crime dramas and horrifying cyberpunk stories.

Even though it would be impossible to adequately summarize the breadth and complexity of German horror films in a condensed list, we can discuss some of the best. These are the top 12 German horror films. These movies all demonstrate how political horror has always been, using the fears and concerns of their respective eras to make a statement about the world we live in. They also demonstrate how important the horror subgenre has always been and will always be to the development of cinema.

Decoder (1984)

Have I mentioned my new death frogs to you? The most bizarre movie on our list is Muscha’s “Decoder,” which combines industrial music, social satire, and neon filters to create a cyberpunk “Alphaville.” Muzak is used at H Burger to keep its customers happy and smiling, where F.M. (F.M. Einheit) works. F.M. creates a noise rock track (which includes the dying squeaks of a death frog) to inspire people to take action against the government and the businesses who seek to dominate them after learning that music is a massive plot to keep people submissive.

It would be “Decoder” if Mario Bava and Andy Warhol collaborated to create the final motion picture in human history. A landfill, a busy fast food restaurant, and a filthy city street are just a few examples of the modern life debris incorporated into the experimental and expressionistic film, which also features brilliant neons and crisp metallics. “Decoder,” a chaotic and chill film, serves as a cautionary tale for oligarchs and a reminder to viewers to be on the lookout for Muzak in their own lives.

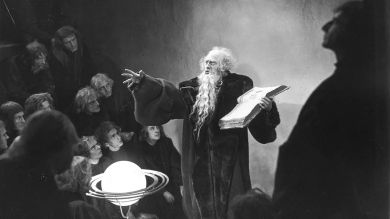

Faust – A German Folktale (1926)

F.W. Murnau’s “Faust – A German Folktale” would be a technological marvel if “How did they accomplish that?!” were a whole movie. The story of an alchemist named Faust (Gösta Ekman), who becomes involved in a wager between Mephisto (Emil Jannings) and an Archangel (Werner Fuetterer), with the fate of the entire world at stake, is told in this movie, which is (of course) based on German folklore and Goethe’s well-known play of the same name. Even though Faust and everyone around him go through a lot of pain, love ultimately overcomes evil.

Even though the movie is almost a century old, its spectacular effects continue to astound and awe viewers. Rings of light surround Faust as he calls Mephisto at a crossroads, moving upward and blazing brightly on his face as they do so. Faust is in a desperate attempt to save his village from a pandemic. When Mephisto makes a deal that Faust can’t refuse, words appear on a blank scroll in a flash of fire and smoke. The stunning use of light and shadow supports a timeless tale of good vs evil with its astounding effects.

M (1931)

“M,” the second Fritz Lang movie to make this list, was the director’s debut sound picture. Edvard Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King” is transformed into the call to death in this crime thriller thanks to the expert use of sound. When Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), a child killer terrorizing Berlin, approaches his victims, he likes to whistle the song. Deci decision to It’s a suspenseful thriller that methodically tightens like a garrote around the viewer’s neck.

The murderer’s insanity, horrifying charm when luring the kids to their deaths, and grief in the face of his would-be executioners are all brilliantly portrayed by Lorre with ferocious determination. He delivers a standout performance, particularly when Beckert is placed on trial by the criminal underworld and the murderer begs for his life, saying he can’t control the urges that cause him to commit his heinous crimes. It’s a terrifying moment, only topped by the opening scene depicting Elsie Beckmann’s disappearance. Lang pans to Elsie’s empty plate at the dinner table, her ball rolling into frame in a field, the balloon Beckert purchased her becoming caught up in some power lines, and then he fades to black as we hear Elsie’s mother (Ellen Widmann) crying her name. More than anything else, it expresses Elsie’s final moments in a sobering, terrible way.

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922)

Even though F.W. Murnau’s adaptation of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” wasn’t approved, it still maintains the record for Stoker’s classic book’s most terrifying motion picture adaption. Thomas Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim), a real estate agent, is hired by Count Orlok (an iconic Max Schreck) to purchase a mansion in Wisborg, the hometown of Thomas. Traveling there with a plague in tow, Orlok sets his sights on Thomas’ young wife Ellen (Greta Schröder), as well as her stunning neck.

The scariest “Dracula” adaption is still Murnau’s, with its spidery lead actor and sinister surroundings. A negative image even seems to imply that the carriage carrying Hutter to Orlok’s castle is traveling through the gates of Hell itself as it appears to teleport forward at times at inconceivable rates. Shadows created by Orlok’s menacing claws appear to have a life of their own. It’s horrifying to watch Orlok carry his coffin with such force and speed, especially as the lid starts to move by itself. Age (and a copyright fight) haven’t made Murnau’s film any less frightful or sharp. It is still unsettling today just as it was more than a century ago.

Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979)

Werner Herzog’s 1979 adaptation of F.W. Murnau’s 1922 masterpiece “Nosferatu” (which is also on our list) approaches the well-known Dracula story in a novel way while still remaining completely original. As a result of his constant boredom, Klaus Kinski’s Count cuts a much more sad figure than many of his previous film counterparts. He bemoans the fact that he cannot age or pass away and declares that the only thing this planet can give him is love, not blood.

Of course, Lucy Harker is the object of his affection, and Isabelle Adjani portrays her as an airy yet grounded individual who is very intuitive, haunted by her love for her husband Jonathan (Bruno Ganz), and terrified of Count Dracula. It’s a captivating performance by an exceptional actress. “Nosferatu the Vampyre” is a “Dracula” adaption for the ages thanks to the unsettling chemistry between Adjani and Kinski and the stunning yet depressing pictures that Kinski and cinematographer Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein capture.

Tenderness of the Wolves (1973)

Based on a true incident, Ulli Lommel’s “Tenderness of the Wolves” portrays the tale of serial killer Fritz Haarmann, who used his ties with the police as an inspector and informant to find victims and conceal the proof of his murders. In addition to surrounding himself with small-time offenders and offering them stolen stuff, Fritz frequently passes off the meat of his victims as pork and lamb that he has “confiscated.” The magnitude of Fritz’s crimes are known to these associates to varied degrees. This movie makes a strong case against collaborators and sympathizers that would have had a significant impact in 1970s Germany.

Fritz is played by writer Kurt Raab, and he gives a seductive and unpleasant performance. Fritz has a peculiar timidity that only serves to heighten the horror of his acts. Raab isn’t afraid to expose the monster hiding beneath Fritz’s affable veneer, but he also isn’t hesitant to acknowledge the charm that has allowed Fritz to get away with his crimes for so long. Fritz is outgoing and amusing, and he makes use of his position with the police force (as well as his friendliness) to his advantage. It’s a disturbing depiction of a terrible individual that makes viewers think of the people who are all around us who are wolves in sheep’s clothes.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

German Expressionist cinema is best represented by Robert Wiene’s cinematic nightmare. The excessive angles appear to be unnatural. Everything is jagged and unsettling, and it all seems to be incorrect. The seams shouldn’t fit together at all. Audiences can relate to it as a metaphor for life: embracing absurdity as truth and continuing to live despite horrific situations. The narrative is no different. Dr. Caligari, a hypnotist (Werner Krauss), uses Cesare, a somnambulist (a fascinating Conrad Veidt), a sideshow attraction, to murder people. The distinctions between life and death, as well as between waking and dreaming, are so hazy that they appear meaningless.

A masterpiece of motion pictures is “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.” Despite being nearly a century old, the cinematography, blocking, and set design seem avant-garde. Even Cesare’s movement seems contemporary. He moves gracefully but inhumanly, attempting to avoid leaving any traces of himself on the earth. As Dr. Caligari is plagued by his thoughts, words can be seen on the screen. The movie makes the unimaginable feasible, leaving viewers questioning their senses and their grasp of reality. It ranks among the most significant horror films ever produced, and its impact is immense.

The Fan (1982)

Simone (Désirée Nosbusch) is completely enamored with R, a pop sensation. She doesn’t eat, sleep, or attend class. She simply strolls through the city while listening to his music and wondering about him. He notices her when she arrives at a recording studio to meet him, and he extends an invitation to his friend’s home. Despite Simone’s claims of love, R maintains that there is nothing more between them than their sexual encounters. The predictable, yet horrible, outcome of Simone’s unwavering fixation with R is what happens next.

The majority of the movie is narrated by Simone in a somnambulant voice while she reads letters she’s sent to R. Even the startling third act is sluggish and hazy throughout the entire movie. The finale is more unsettling as a result of the meticulous pace. Despite Simone’s terrifying preoccupation, it is difficult to regard her as a villain because of director Eckhart Schmidt’s efforts to put the audience in Simone’s position. Our sympathies are more with Simone than with anyone else in the movie because we see her being victimized by men repeatedly throughout the movie, including her neglectful father, postal workers who tease and jeer at her for waiting for responses from R, a man who picks her up hitchhiking and tries to rape her, and R himself. It’s a frightening environment for the audience to be in, which makes the German horror movie “The Fan” memorable and extremely thought-provoking.

The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920)

This vintage Jewish horror movie was co-directed by Paul Wegener and Carl Boese. Wegener portrays the title character in “The Golem: How He Came into the World,” which Rabbi Loew (Albert Steinrück) creates from clay and then brings to life through a mystical ceremony that conjures a spirit. The Holy Roman Emperor wants to expel all Jews from their homes in Prague, and the Rabbi utilizes the Golem to protect the Jewish people from his decrees. The idea initially succeeds, but the Golem eventually comes under malevolent control and turns against his builder and the people he was supposed to save.

James Whale’s “Frankenstein” clearly predates “The Golem: How He Came Into the World.” Even the cinematographer, Karl Freund, worked on both movies. “The Golem” established the tone for subsequent horror films and is still regarded as one of the best Jewish horror movies in history thanks to its ominous visuals, powerful performances from the menacingly stoic Wegener and the desperate Steinrück, and macabre tale of a man bringing an inanimate creature to life before losing control of it.

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933)

There is a good reason why two works by Fritz Lang are included here. This cinematic maestro is responsible for many works of art, including the seminal science fiction movie “Metropolis.” The titular Dr. Mabuse (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) is imprisoned in a psychiatric facility in “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse,” the follow-up to his silent film “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler.” Although he still has power over the criminal underground, Mabuse starts a systematic reign of terror in an effort to bring down the entire system and seize it for himself.

“The Testament of Dr. Mabuse,” which was outlawed by Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda, is a disturbing analysis of the evil power that Hitler held as well as an ominous forecast of how that power spreads through followers who are “only following orders.” In 1933, Lang wasn’t a fortune teller. He only recognized the Nazis for what they were, and his movie emphasizes the value of using all of your resources to combat that encroaching evil.

Vampyr (1932)

The liminal nature of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s (very successful) attempt to bridge the gap between the new technology and the visual lexicon of silent cinema is a wonderful fit for the unnerving character of a vampire tale, and “Vampyr” was his first sound film. In the movie, Allan Gray (Julian West) is on the road close to the village of Courtempierre when he receives a suspicious package from a mysterious man who instructs him to open it after his passing. Gray follows his wanderings to a manor, where he sees the man being killed. He finds a book on vampires inside the parcel when he opens it, which launches him on a perilous and horrifying investigation.

The effects in “Vampyr” are just as breathtaking as those in “Faust” by Murnau, but “Vampyr” takes the top rank on this list thanks to its elegiac lyrics. In Dreyer’s hands, legendary cinematic sequences include shadows dancing along a riverbank, a man viewing his own funeral procession through a coffin window, and a weather vane silhouetted against the sky. Dreyer was a master of his craft (his “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is one of the greatest movies ever made, sound or silent), and “Vampyr” is the greatest German horror movie ever because of his ability to create unforgettable pictures with light and shadow.

Vampyros Lesbos (1971)

Jess “Jess” Franco’s iconic vampire movie is a fascinating investigation of desire and restraint. It is stylish and sensual. Countess Nadine Carnody (Soledad Miranda) entices attractive women to her Turkish estate, which also happens to have once belonged to Count Dracula, especially blondes because she has a thing for them. Linda Westinghouse (Ewa Strömberg), one of her targets, overhears the Countess doing a sensual lesbian floor show one night and finds herself intrigued and drawn to her. Linda discovers the Countess is a vampire when she visits her at her estate. She then has to choose whether to become into a vampire herself or go back to her previous life.

Slow and dreamy, “Vampyros Lesbos” weaves long love scenes with trippy music. While some viewers might object to the film’s plodding pace, the overall result is a wonderful hypnotic state that mimics the Countess’ persuasive abilities. When Linda wakes up in a hospital and encounters Agra (Heidrun Kussin), the Countess’s former lover who has been institutionalized for her infatuation, the movie looks into the stigmatization of homosexuality, especially in women. Even if the Countess’s story does not have a happy ending, neither she nor Linda are held accountable for their desires. It implies that Linda’s experience is much more than just a dream and that it will follow her throughout the rest of her life.