While new films can be influential for the medium, it’s much more probable that older films will take the lead (but keep an eye on this space for the most significant films of the twenty-first century). They did it first after all. Although later films could be more visually appealing or entertaining, there is a clear distinction between “the best” and “the most important.”

As a result, these aren’t really family films, but that’s absolutely fine because films don’t always have to be serious. These films, however, are for cinephiles and filmmakers. Although there is some overlap, these films were the best at influencing others; they were the ones that walked while your favourites ran; they are the most significant films that have ever been produced.

8½ (1963)

The famous Sunset Boulevard and Sullivan’s Travels are two examples of films about films that were made before 812, but it wasn’t until the dreamy, angst-filled Federico Fellini picture that they truly formed a genre unto themselves.

In a similar vein, while filmmakers had dabbled in heavily autobiographical works about themselves, Fellini inspired a whole wave of filmmakers to make films about struggling filmmakers trying to make films, including Woody Allen (in his 812 rip-off, Stardust Memories), Truffaut (in Day for Night), and pretty much every other director to emerge in the past 30 narcissistic years. All artists would be drawn to Fellini’s strange scenes, mixtures of sex and grief, and meta-meditations on films.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

From comedies like Dr. Strangelove through historical epics like Barry Lyndon and, of course, science fiction with the timeless masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick continuously revolutionised genres. One may argue that 2001 was the first major sci-fi movie made in the modern period. With its psychedelic exploration, it wonderfully captured the hippy-dippy era’s dreamy hippy-dippy vibe.

This picture about a compromised expedition to Jupiter is full of delicacy and truly magisterial direction, but it’s the ground-breaking special effects and avant-garde conclusion that give it such a crucial significance.

A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

A Streetcar Named Desire would be a very good movie that easily could have remained a Tennessee Williams play without its complex psychological plot and stunning dialogue, but it is the specifically cinematic acting that makes this one of the most significant movies ever made. Even if the entire cast is nearly flawless (Vivien Leigh, Kim Hunted, Karl Malden, Peg Hillias), A Streetcar Named Desire has what might be Marlon Brando’s Stanley Kowalski as the most significant performance in cinematic history.

While Brando had already displayed his talents on film in The Men, he did it here while also performing in William Shakespeare’s play, fusing his stage and film acting backgrounds to create modern film acting. The New Hollywood movement and actors like De Niro, Pacino, Hackman, and Hoffman were made possible by Brando’s performance, which introduced Hollywood to the authenticity, spontaneity, and neurotic tension of real life acting.

All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

Lewis Milestone, one of the hardest working directors in entertainment, was a master of cinematic adaptations and this is his best. He also directed Of Mice and Men, Mutiny on the Bounty, and The Front Page, all classics, and this is one of the first great war films, All Quiet on the Western Front, an emotionally powerful and cinematically riveting account of young men on the battlefront in World War I.

The American epic follows students as they transition from idealists to traumatised, disillusioned veterans in the war’s front lines and trenches. Every anti-war movie’s worldview, as well as practically every war movie’s technical aspects, have been impacted by All Quiet on the Western Front. Even though it was created in 1930, it must still be seen.

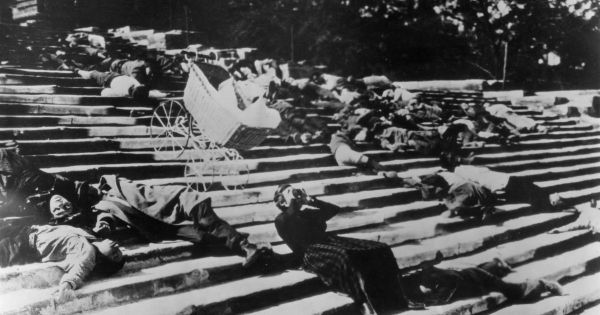

Battleship Potemkin (1925)

Although montage wasn’t invented by Sergei Eisenstein, he did master it in a way that showed aspects of film that had never been seen before. Eisenstein introduced Marxist materialism to cinema through the dialectics of editing, blending shots with reverse-shots to create larger, more potent sequences. He did this with a higher emphasis on editing and camera angles than previous directors.

The Russian Navy mutiny that set off the Russian Revolution and the creation of the Soviet Union was dramatised in the early masterwork of Soviet cinema, Battleship Potemkin.

Breathless (1960)

Regarding the French New Wave, many people believe that it divided into two main strands: Jean-Luc Godard’s more experimental and political films, which reinterpreted Hollywood history in the particular context of the 1960s France, and Francois Truffaut’s more spontaneous, emotional, and romantic films. Breathless (or bout de souffle), Godard’s first feature film, became instantly renowned before he entered politics.

The film, which stars the utterly endearing Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg (whose iconic pixie cut impacted fashion forever), is a jump cut-filled examination of cinema, youth, and dreamers that follows a minor criminal as he haggles and falls hopelessly in love with a newspaper girl. Breathless revolutionised filmmaking with more intensity in the first 10 seconds than most entire films had.

Citizen Kane (1941)

Yes, this is one that we are all aware of. Even if many people rightly believe Citizen Kane to be the best movie ever produced, it doesn’t negate the reality that it changed the language of cinema forever. However, by this point, we’re all probably sick of hearing about Citizen Kane.

Double Indemnity (1944)

Double Indemnity is a brilliant portrayal of misdirected impulses and obsessive obsession by Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler. It is one of the finest film noirs and one of the first genuine ones. A femme fatale wife (a flawless Barbara Stanwyck) and the chump who falls hard for her (a perfectly average Fred MacMurray as an everyman sadsack) plot to kill her husband so they may collect insurance money in the movie.

After World War II, a wave of cynical, nihilistic masterpieces that challenged the notion of American exceptionalism and moral absolutes began with Double Indemnity. While other 1940s film noirs may have been superior (Out of the Past) or stranger (D.O.A. ), Wilder’s Double Indemnity arrived first and elevated the genre with a faultless script. In this funny, caustic classic, Edward G. Robinson offers one of the greatest performances of all time as an insurance investigator.

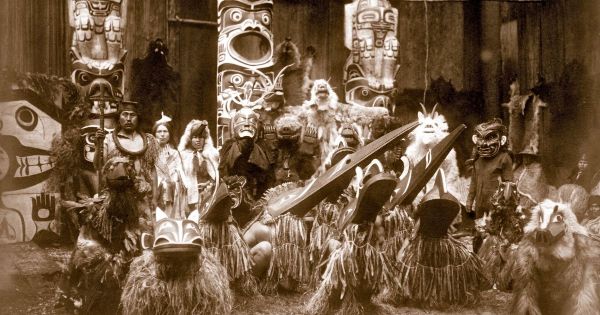

In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914)

In the Land of the Head Hunters was the first documentary to do it, and it did it surprisingly successfully. Later documentaries like Nanook of the North and The Great White Silence would understandably garner more attention. The Kwakwakawakw people of British Columbia were the subject of Edward Curtis’ eerie, unsettling film, which was made a dozen years before the term “documentary” was ever developed.

In the Land of the Head Hunters humanises the people in a way that was much more empathetic than other ethnographic short films and studies, despite the fact that it is technically scripted, just like most early documentaries were. The movie also chronicles many of the authentic rituals, outfits, and works of art of the culture.

Intolerance (1916)

D.W. Between 1915 and 1921, director D.W. Griffith had an incredible run, creating numerous works of art that would permanently change how films were made. Although Birth of a Nation was his first great epic, its tarnished reputation limits it to merely being of scholarly relevance. His subsequent picture, Intolerance, is still his best; it makes the most of the cinematographic experiments he started with the available technology within an anthologized story that is both fascinating and moving.

Ironically far away from the horror of Birth of a Nation, Intolerance was an examination of injustice throughout human history, from Babylon to modern-day California, and it is still emotionally powerful today. It’s perhaps the first ideal epic with its expertly produced dolly shots, enormous sets, and legions of extras.

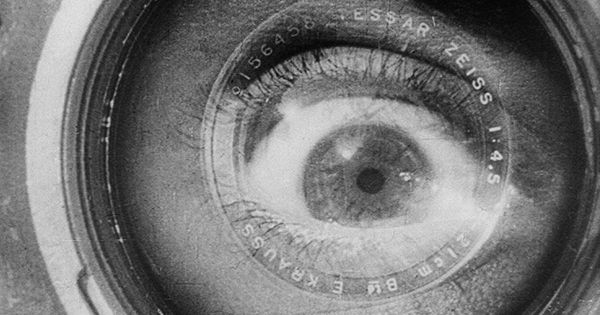

Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

The Soviet masterpiece Man with a Movie Camera is another experimental movie, but it has an entirely different aesthetic and drive than Un Chien Andalou, and it possibly has the most cinematic invention of any movie. Dziga Vertov explored with technology and the processes involved in making films, as opposed to the previous film, which focused more on ideas and pictures.

This incredibly meta film about a cinematographer filming different areas of Moscow, Kyiv, and Odesa incorporates and innovates on match and jump cuts, fast and slow motion, Dutch angles, split screen, numerous exposures, and stop-motion animation.

Metropolis (1927)

Fritz Lang invented many of the cinematic techniques that would come to characterise science fiction for many years with Metropolis. The German film, which masters early clichés like androids or cyborgs, dystopian futures, and the struggling proletariat beneath a glittering veneer, is sort of the ‘Ur’ sci-fi book for cinema.

In the 1930s, Metropolis utilised miniatures in a way that helped to inspire fantastic fantasy and science-fiction films like King Kong and Things to Come. The future world Lang and his team imagined is painstakingly detailed, with the underclass toiling away before employing a potent android to overthrow the upperclass.

Nosferatu (1922)

Nosferatu, arguably the most famous silent horror movie, was made by loosely adapting Bram Stoker’s novel to convey the story of a vampire entering a small town and stalking a young woman. Although horror has been a part of film since its inception in the late 19th century and had the power to scare audiences then, most viewers now find it difficult to connect with the horror because of the archaic technology.

However, Nosferatu is still incredibly spooky today, and it had a significant impact on the development of atmosphere and jump scares throughout the following century. This is partly due to F.W.’s excellent direction. Murnau, who produced some of the best films of the 1920s, but Max Schreck’s outstanding performance, which was so unsettling that some genuinely believed he was a vampire, provides the majority of the frights. Even today, 100 years later, Nosferatu still frightens people.

Rashomon (1950)

With his brilliant film Rashomon, the legendary Akira Kurosawa contributed to the introduction of unreliable narrators, postmodern subjectivity, and ethical ambiguity in cinema. Though it may not be as cool, grandiose, or passionate as some of his other films, this one’s examination of memory and deconstruction of narrative make it a universal classic with unending influence.

The story revolves around three separate witnesses testifying at a trial and providing three distinct narratives of the same crime, each of which clarifies and complements the others while obscuring other aspects of the reality. Rashomon is a compelling experiment in storytelling that makes beautiful use of rain and features a crazy performance from Toshiro Mifune.

Rome, Open City (1945)

Roberto Rossellini’s masterpiece, Rome, Open City, was possibly the first post-war masterpiece, studying the trauma and destruction that were left in the wake of World War II. Rome, Open City follows the Resistance against German Nazis and Italian Fascists in Rome around 1944 as the losing side becomes more violent and desperate, and is primarily focused on a priest who is determined to help and save as many people as possible.

While Umberto D., Paisa, or Shoeshine may be better Italian Neo-Realist films, and this one is more stylized and melodramatic than most, its significance comes from its historical setting and proximity to the tragic theme of war. Rome, Open City, a documentary that was shot in the run-down streets and showed how disturbed Italy and the rest of the globe were after the war, is still incredibly moving.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937)

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs broke the creativity dam for animated pictures, steadily overwhelming the market. Three years later, Walt Disney would do a greater job with Fantasia. Thanks to its charming music and language, stunning animation, and truly innovative storytelling approaches, the first Disney feature-length picture continues to rank among its greatest. In a sense, this movie is responsible for all animation.

Stagecoach (1939)

The Wild West has been portrayed on film ever since 1903’s The Great Train Robbery, but not in any great depth until the late 1930s. This is due to the fact that silent Westerns were frequently very cheap and tacky, and that when talkies came out, movie studios abandoned the genre because it was simply too expensive. Though a number of legendary films, including Jesse James, Dodge City, and Destry Rides Again, were released in 1939, it was John Ford and John Wayne’s masterwork Stagecoach that completely altered the course of events.

The director’s methods for filming Western action and balancing landscape photography with medium shots and close-ups would define the visual language of Western films for years to come. Wayne’s perfectly matched performance and Ford’s imagery in Stagecoach would instantly become iconic. Wayne’s performance in this movie would serve as a model for almost every Western hero for decades.

The 400 Blows (1959)

Along with Pather Panchali and Little Fugitive, The 400 Blows, one of the first films to take a true, sincere look at childhood, was one of the first to usher in the perennially inspirational French New Wave. The movie centres on a young Alain Delon, who is unable to stop acting out in class, feels ignored at home, and feels cut off from the rest of humanity. Over the following 20 years, Truffaut would make four more films about the exuberant and mischievous Delon, all starring the great Jean-Pierre Léaud. Delon is such an iconic personality.

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland in The Adventures of Robin Hood, 1938, Warner Bros.

At the end of the 1930s, a variety of visually breathtaking pictures, ranging from Gone with the Wind and +9 to Mystery of the Wax Museum and Doctor X, were produced thanks to the gradual perfection of colour cinema after years of trial and error. There is a tonne of competition, but The Adventures of Robin Hood may stand out from the crowd thanks to its vivid Technicolour colour scheme.

Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, Basil Rathbone, Claude Rains, and Alan Hale all give endearing performances in Michael Curtiz’s classic, which was the first major motion picture for Warner Bros. and is still enjoyable and exciting 85 years later.

The Phantom Carriage (1921)

With the wonderful, truly haunted movie The Phantom Carriage, Victor Sjöström created a brand-new aesthetic with camera trickery and brilliant editing. Along with other ground-breaking special effects, Sjöström and his cinematographer Julius Jaenzon helped create a lot of the horror, fantasy, and magical realism that we know and love today. They did this by using double exposure in-camera with many layers.

In The Phantom Carriage, a spooky New Year’s tale is told across winter Sweden, with the last person to pass away before the clock strikes midnight being cursed to collect the souls of those who pass away throughout the coming year.

The Seventh Seal (1957)

The flattening effect of the silent era, which homogenised nationality by requiring only text and images, undoubtedly contributed to the popularity and acclaim of international cinema. However, it wasn’t until director Ingmar Bergman and particularly The Seventh Seal that international and ‘arthouse’ cinema became widespread, significant, and even lucrative. The year Seventh Seal was released, the Academy Awards established the Best Foreign Language Film category, and filmmakers and artists all around the world would be influenced by its incredibly distinctive aesthetic.

The sombre existential exploration and private chamber dramas of Bergman served as the ideal counterbalance to the upbeat Technicolour of 1950s Hollywood, and many individuals discovered cinematic honesty and integrity for the first time abroad. The Seventh Seal, which follows a soldier returning from the Crusades who plays chess with Death and travels Sweden with a group of artists and performers amid the bubonic plague, perfected the now-cliched and mocked arthouse ideal of sombre meditations on death. Contrary to popular belief, the film is actually much funnier and more intriguing than it frequently is. However, what really set it apart from other films was its distinct foreign flavour and philosophy.

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

The Wizard of Oz is a visually spectacular, subtly unsettling spectacle of the greatest calibre. It is an enormously imaginative and magical work. By anthropomorphizing its dream environment and populating it with vibrant, enduring people, The Wizard of Oz taps into the inventiveness of youth by essentially building an entire universe within the young protagonist’s mind. Even though the production was a dreadful nightmare, the picture is simply technical (and musical) perfection and is loved by both children and adults.

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

Trouble in Paradise paved the way for intelligent comedies that valued dialogue, romance, and plot over slapstick and narrative justifications for set pieces before other quick-talking classics like It Happened One Night and His Girl Friday came along to steal its thunder (not that there’s anything wrong with that; Our Hospitality, Sherlock Jr., or The Gold Rush could certainly be added to this list).

This endearing early talkie was directed by Ernst Lubitsch, the first great master of rom-coms, and it benefited enormously from being released prior to the Hays Code’s strict restrictions on sensuality and “immoral” behaviour on screen. In this amusing early treasure, two criminal lovers attempt to con a wealthy woman working at a perfume firm, but romance complicates matters. It has the same sense of vitality as contemporary rom-coms like Crazy Stupid Love or Sleepless in Seattle.

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

Un Chien Andalou, often known as An Andalusian Dog, was perhaps the first Surrealist film produced by the great Luis Buuel and Salvador Dal. There isn’t really a story here; instead, there are a number of iconic, maybe metaphorical scenes that play with both form and subject while producing unforgettable imagery (from ants on a hand to possibly the most iconic picture in cinema, an eyeball with a blade poised to sever it). Future audaciously experimental films like Meshes of the Afternoon, Dog Star Man, and La Jetée would be influenced by Un Chien Andalou.

Within Our Gates (1920)

For a very long time, the great Oscar Micheaux was kept out of the canon of cinema, but in recent years, some beautiful reissues have helped more people become aware of the first truly great Black filmmaker. Working outside the studio system, Micheaux’s independent films emphasised working class people of colour and female characters, two things we didn’t see in Hollywood.

With the exception of the now-lost The Homesteader, Within Our Gates was Micheaux’s debut movie and it continues to be one of his most important and riskiest works. The story revolves around Sylvia’s (a heartbreaking Evelyn Preer) struggles as she endures institutional racism through a string of catastrophic incidents, romantic relationships, and arbitrary violence.