In the eyes of many, Charlie Chaplin represents old Hollywood; they have little understanding or respect for his contributions to film history. The London native’s on-screen presence as The Little Tramp will always be associated with him, but the role was only a small portion of an extraordinary career that few people are fully aware of. The 1992 movie Chaplin, starring Robert Downey Jr. in the title character, gave audiences a glimpse into his turbulent personal life, but many younger moviegoers are unaware of the breadth of his filmography.

Chaplin was a talented dramatic actor who was more than just a humorous performer. Many of his classic pictures were also written, produced, and directed by him, displaying a vision and creativity uncommon in early Hollywood. Due to his political views, the United States threatened to cancel his visa and prevent him from entering in the 1950s. Chaplin limited his cinematic career by choosing personal exile and delaying his return to America for more than 20 years. Finding (or revisiting) Chaplin’s work is thankfully easy because several of his films are already streaming, most notably on HBO Max, and the legendary Criterion Collection has many of his classics accessible on disc and on their own streaming service.

These are ten of Charlie Chaplin’s best full-length movies from his career of more than 50 years.

A King in New York (1957)

It’s a tragic comedy. The final leading role for Chaplin would be in A King in New York, which has a lot of social satire. Chaplin portrays a fictional country’s overthrown monarch who escapes to New York without a penny to his name. The King finds himself reneging on his values while attempting to fit into contemporary American culture after an unexpected television appearance makes him a star.

The movie is a great illustration of how Chaplin’s humour developed after World War II and The Great Dictator, and there is some biting criticism on politics, McCarthyism, and the nature of celebrity. The movie merits being listed among the top comedies from the 1950s due to its growing reputation.

City Lights (1931)

The Tramp falls in love with a blind flower girl (Virginia Cherrill) in Chaplin’s classic silent film City Lights, and he struggles to raise money for a surgery to give her back her sight. His luck changes when he stops a wealthy guy (Harry Myers) from attempting suicide while intoxicated. The two become friends, but the wealthy man only acknowledges him when he’s intoxicated, which causes a variety of issues and inspires some funny scenes.

Despite the fact that Chaplin is rarely listed on lists of the best comedy film directors, he should be. The boxing bout at the climax of the movie, which is the most enduring comedy bit in the entire movie, took a week to shoot due to Chaplin’s obsession with perfection. Albert Einstein attended the Los Angeles premiere of the movie and is said to have sobbed in public after watching the last scene.

City Lights was the highest-grossing silent movie of 1931, a year when talking movies were popular in theaters, despite being a silent movie. It was ranked as the top romantic comedy and the tenth most romantic movie of all time by the American Film Institute.

Limelight (1952)

In Limelight, Chaplin plays an aging comedian who is long past his peak, making an attempt at an autobiography. As Tynan Yanaga of Film Inquiry puts it, it may have been an effort to legitimize his life and achievements while also serving as a reminder to viewers of his real-world grandeur. After Chaplin’s character Calvero prevents a suicidal ballerina (Claire Bloom) from taking her own life, they start a platonic relationship that is frequently tense as she rises to fame while he continues to have a waning career. The point is that they are not your typical romance movie pair.

There are various “performance” scenes that serve as a reminder of Chaplin’s mastery of comedy, and Buster Keaton himself joins Calvero on stage for these scenes. Sydney Chaplin, the real-life son of the actor, gives a terrific performance in a supporting part. Perhaps a foreshadowing of the curtain call Chaplin anticipated for himself is the tragic, bittersweet conclusion.

Strangely enough, Chaplin received his first and only non-honorary Oscar for the movie’s Best Original Score; nevertheless, he received it in 1973, 20 years after the movie’s debut. This was due to the fact that Limelight didn’t hit American theaters until 1972, when it became eligible for the Oscars, as a result of his self-imposed exile.

Modern Times (1936)

In Chaplin’s ode to the working man, Modern Times, the Tramp attempts to build a life with a young street urchin while falling in love with her (the stunning Paulette Goddard). Chaplin was in his mid-forties at the time, and Goddard, who was 25 at the time, plays an underage girl, making the love film combination more than awkward. The humour in the movie, however, is centered on the struggle against authority and the demands of work from soulless corporations, while the love parts are kept relatively pure.

A highlight is the hilarious set pieces at the art-deco factories. The movie opts for a hopeful rather than a happy ending as a reflection of the Great Depression era it was released in. In the closing scene, Chaplin and Goddard travel in pursuit of a better life but still holding out hope for finding a house and happiness in the future. Not only is Modern Times one of the best comedy ever created, it is also one of the best classic comedies of all time.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

Chaplin’s sequel to The Great Dictator, which came out seven years later, took a drastically different turn. In the brilliantly comic black comedy Monsieur Verdoux, a serial murderer marries numerous women around France before killing them for the cash.

Orson Welles provided the idea for the movie, which Chaplin wrote and directed. Chaplin maintains a lighthearted tone throughout, even as he introduces his killer persona and criticizes the political and economic structures of the globe. One of Verdoux’s many wives, played by Martha Raye, steals the show because of her brazen personality, which is a better match for his plots. Chaplin was nominated for an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for the movie, but he did not take home the prize.

The Circus (1928)

The Tramp, who is running from the police in this vintage silent comedy, joins a circus and falls in love with the owner’s stepdaughter. The Circus is unexpectedly poignant because Chaplin gives his character more nuance. When a rival for the woman The Tramp is smitten with arises, The Tramp becomes envious and possessive, giving the movie a romantic screwball comedy vibe. The Academy revoked Chaplin’s Best Actor candidacy and instead granted him an honorary Oscar for his contribution to the movie.

Chaplin, who was always meticulous, reshot a famous scene in which he is imprisoned in a lion’s cage over 200 times to get the action just right. The lion was actually in the cage in several of the takes, so his terror was real. Watch out for Tiny Sanford, the actor who portrays the circus property manager. His imposing size made him the ideal straight man for Chaplin’s physical jokes in no fewer than eight of the actor’s appearances in his features and short films.

The Gold Rush (1925)

Chaplin’s Tramp is a character who sets out to find his fortune during the Alaskan Gold Rush but instead discovers despair and misfortune. He develops feelings for a girl in the town’s dance hall, but even that is not without its challenges. The movie demonstrates the breadth of Chaplin’s comedic mastery of physical gags, including a scene in which he cooks and consumes his own shoe and another with a hut perched precariously on a cliff. In the categories of Best Musical Score and Best Sound Recording of Music, the movie received two Oscar nods.

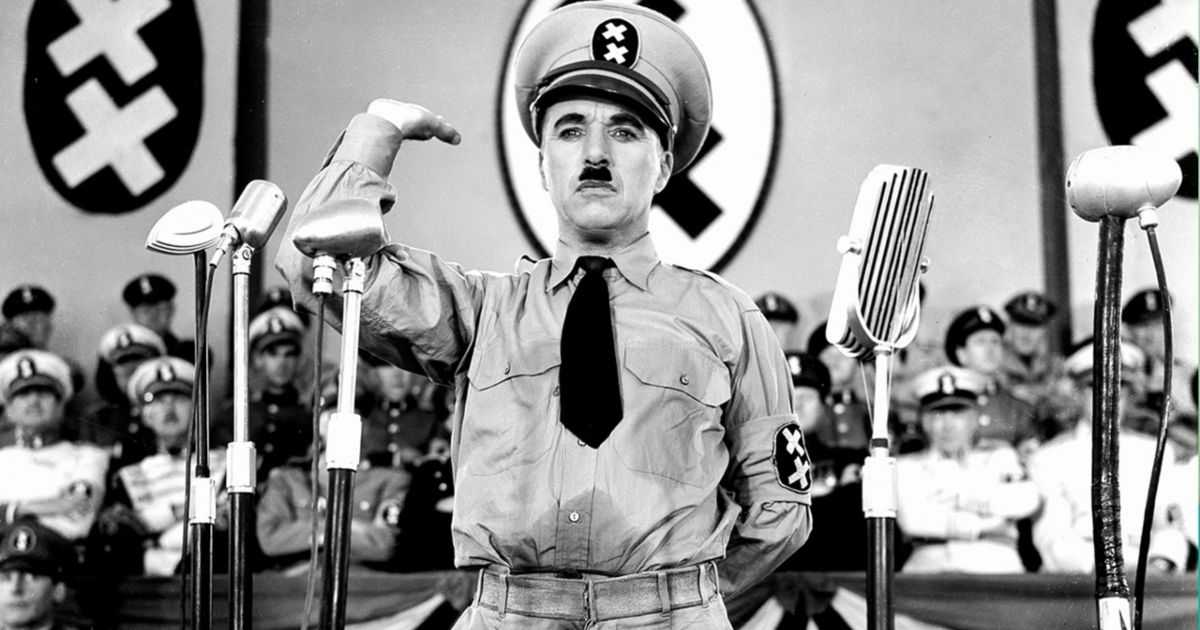

The Great Dictator (1940)

Most Americans and Britons opposed World War II intervention in the middle of the 1930s, favoring appeasement over direct confrontation with Hitler. By the time The Great Dictator was released in 1940, Britain had already entered the war, but America still needed persuasion. It was Chaplin’s attempt to alter attitudes. Adenoid Hynkel, the dictator/ruler of Tomania (and a direct dig at Hitler), and an unnamed Jewish barber who suffers under Hynkel’s antisemitic rule but who bears a striking resemblance to him, were both played by Chaplin in the political satire. By a stroke of luck, the barber is mistaken for Hynkel and given the opportunity to make a speech that could alter the course of history.

One of the most poignant speeches in movie history, the speech at the movie’s conclusion still has meaning today. Hannah, the feisty Jewish girl who stands up to Tomania’s stormtroopers, is perfectly played by Paulette Goddard, Chaplin’s wife who appeared in Modern Times four years earlier. The Great Dictator, one of the best comedies from the 1940s, is unquestionably a must-see. The movie received five Oscar nominations, including Best Picture and Best Actor, but none of them went to the movie.

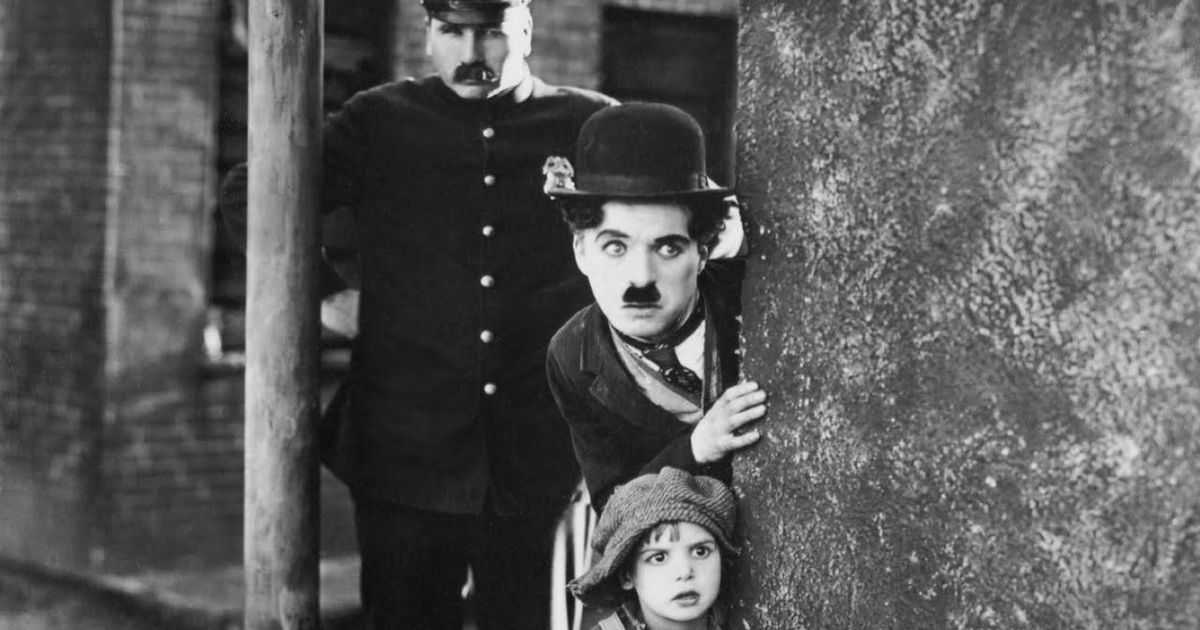

The Kid (1921)

It’s incredible to think about how Charlie Chaplin used the persona of the Tramp to produce a lot of timeless movies, consistently producing top-notch humor. One of Chaplin’s best silent movies, The Kid from 1921, features the Tramp adopting and raising an abandoned child until events endanger their bond. Jackie Coogan, who played the Kid, later rose to fame in the 1960s television series The Addams Family as Uncle Fester.

The Kid is one of the select few movies to receive a flawless 100% score on Rotten Tomatoes, and it merits that distinction. Although we rank it in the middle of Chaplin’s best movies, Rotten Tomatoes is not always wrong. It just serves as evidence that his earlier films are deserving of similar praise.

Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914)

The distinction of being the first comedy to last an entire feature length belongs to Tillie’s Punctured Romance. Before it debuted in 1914, Chaplin had produced more than 30 comic shorts, the majority of which starred his Little Tramp persona. But in this movie, he portrays a cunning con artist who marries Marie Dressler, the daughter of a rich farmer and heir to a sizable fortune, in order to steal her money.

The movie finishes with a confrontation and an appearance by the Keystone cops, and Chaplin infuses elements of his Tramp impression into his persona. Chaplin just has a supporting role in the film, which is a little too long, but he makes the most of it.