Italy was deeply affected by the Second World War and was undergoing reconstruction in the middle of the 1940s, like many other European countries. While being on the winning side of the fight made it much simpler to return to what was perceived as routine for nations like France or England, the main ally of the Third Reich for the most of the war, the aftermath caused the entire nation to doubt itself.

This was also true of the cinema. The ‘Telefono Bianchi’ (White Telephones) movies dominated Italian cinema in the years before and during the war. These were a parody of the era’s American comedies. These movies had opulent, pricey Art Deco set designs with affluent people living in them. They supported traditional values, deference to authority, and a strict class structure that was consistent with the fascist dictatorship.

Bellisima

Neorealism was no longer a new trend by 1951; it had become Italy’s dominant film aesthetic and was having an impact on the rest of Europe and the rest of the world. Then, Luchino Visconti created a meta-narrative about the state of the Italian cinema industry and how Neorealism inspired common people to dream of appearing in movies and transcending their material circumstances. In Bellisima, a stage mother makes a desperate attempt to force her daughter to attend a movie audition. The film, which has a comic undertone, exposes the truth of how movies that were once intended to be tiny and personal have grown into a global phenomenon and changed into something entirely.

Best Italian Neorealism

The Italian reality was not portrayed in this cinema. These images of affluent people were very different from the majority-poor rest of the nation. The films’ carefree outlook was blatantly hypocritical to the society from which they sprang, and by 1940, as World War II broke out, the Calligrafismo school of filmmaking had taken off. It was a very different method of filmmaking. Calligrafismo, while not a direct response to the White Telephone movies, concentrated on formalist elements and improving Italian cinema’s overall calibre to compete with the rest of Europe.

The genre was viewed as artificial and superficial because the filmmakers who created it sought to create works that went beyond fascism but had little interest in depicting the realities of their own nation or any sort of societal devotion. A new generation of filmmakers developed their art through these productions by working on many of these films, and by the time their nation was freed, they were prepared to realise their own ideas.

They began telling tales of common people, the ongoing fight of the working class, and the poetic trials of life on the streets with little to no funding or equipment. Italian Neorealism emerged as a more realistic method of filmmaking that mostly employed untrained performers, shot nearly exclusively on location, and produced sequences based on everyday occurrences.

As the genre developed, it grew less uniform and focused on a variety of traits and more of a link between cinema techniques and the post-World War II social realities in Italy. These movies had a significant impact on future generations, and Neorealism is largely responsible for what we now witness in independent film. Here are the top 15 movies in this category that helped make movies seem more real and human.

Bicycle Thieves

One of the best movies ever made is still the most well-known Neorealist film. The best film by Vittorio De Sica has endured the test of time and will always stand as one of the most harrowing and tragic depictions of life’s inequities. The book Bicycle Thieves depicts the tale of Antonio, whose family relies on him to transport food and shelter. Together with his son Bruno, they search the streets of Rome for it when it is stolen. As the movie goes on, both the father and the son must work to maintain their resolve in the face of losing their primary source of support as well as a society that increasingly seems to care little or nothing about them.

Europe ’51

The Neorealist films started to address not just the life of the working class but also their relationship to those who have a more favourable socioeconomic status as Italian society started to make sense of itself again. The addition of professional performers, in Rossellini’s case, his then-wife Ingrid Bergman, is another example of how the genre has evolved. In the film Europe ’51, an affluent socialite loses her kid and, overcome with remorse, resolves to dedicate her life to helping the sick and destitute, a decision that is not approved of by her husband.

Germany, Year Zero

Italian Neorealism placed a lot of emphasis on children. They typically play supporting parts in the first movies in the genre, seeing the trials of adulthood. As observers of the problems of the present, they hold the key to the future. In the concluding chapter of his war trilogy, Roberto Rossellini tells a tale of empathy and sorrow from the viewpoint of a little boy.

In the book Germany, Year Zero, a young German child named Edmund struggles to deal with his complex and impoverished family in the years following World War Two. Rossellini depicts the inner dynamics of a broken-down German society in one of the rare films of the genre that is not set in Italy.

I Vitelloni

Director Federico Fellini served as Roberto Rossellini’s student before going on to become the most celebrated Italian director of all time. Rossellini was one of the most important characters in Italian Neorealism. In the early stages of his successful career, Fellini wrote the screenplays for several Rossellini movies, garnering him his first Oscar nominations for Rome, Open City, and Paisan. From there, he rose to the pinnacles of the movie industry.

One of his early films is unquestionably related to the movement, while not being regarded as an official member. I Vitelloni tells the tale of five young friends who drift aimlessly through life after having their childhoods affected by the war.

Miracle in Milan

Vittorio De Sica was attempting to use a fantasy story to connect children’s literature with social realities when Joseph Burstyn Inc. Miracle in Milan was published. A little child is rescued in a cabbage patch by an elderly woman, and after she dies, her ghost gives him a dove, enabling him to work miracles for the underprivileged people he lives with. The dove refuses to leave his side even after the angels decide to take away his powers since it has seen his heartfelt plea for fairness and equality.

Ossessione

Ossessione, widely regarded as the first movie of its kind, introduced the world to Luchino Visconti, who would go on to make some of the best and most ambitious movies ever made. The movie is the first to start presenting characters outside of bourgeois contexts, despite the fact that some reviewers classify it as part of calligrafismo and despite the fact that it does share many of its traits. A vagrant and an innkeeper who start dating and scheme to have an affair are the story’s primary characters.

Visconti managed to make it all the way to the premiere before running into difficulty, having the movie banned and having all the negatives asked to be destroyed. The fascist administration had been strongly against the movie since pre-production. He fortunately retained one to himself, from which all subsequent prints were made.

Paisan

Roberto Rossellini depicts the life of common Italians as the Allies retake Italy from the fascists in one of the strongest movies on our list. As the second film in his war trilogy, Paisan illustrates the cultural divide between the Anglo-Saxon culture and Europe and serves as a link between the director’s depictions of wartime Germany and Rome.

A year after the war’s end, Rossellini’s film is sensitive and well-informed; events that had recently torn humanity apart are now part of history, and his meticulous attention to detail provides a magnificent portrayal of what the end of conflict meant for humanity.

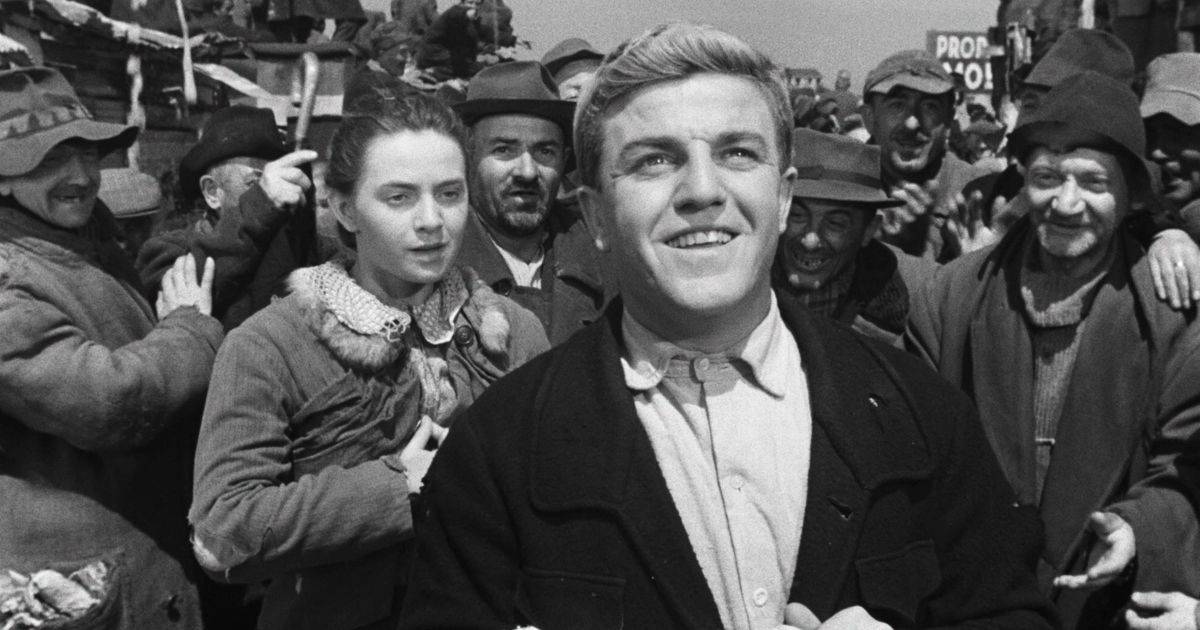

Riso Amaro

Giuseppe De Santis was the Neorealist who was most adamant and passionate about changing and improving society. One of his earliest films was titled Riso Amaro (Bitter Rice), which is also a verbal pun on the word riso, which has two meanings in Italian: rice and laughing. The story revolves around two robbers who disguise themselves as rice workers to flee the law, and the issues that arise when they meet a man and a woman in the plantations. De Santis offers an ode to the Italian lady of the post-war era by emphasising the disparate landscapes of rural and industrial northern Italy, as well as the differences and parallels in social interaction.

Roma 11:00

Rome 11:00 tells the tragic tale of what happened before, during, and after a staircase accident and is based on a true occurrence. focusing on five girls out of 200 who responded to an advertisement for a secretarial employment and how they handle the overcrowding in the facility. The film focuses on the harsh post-World War II conditions in Italy, what work meant in that environment, the lives of the women trying to survive in this new world, and how life’s cruelty causes individuals to turn against one another.

Rome, Open City

Italy was only partially under the authority of the Allies in 1943, and the government, aristocracy, and military quickly took action to restore calm to the country. German military forces invaded Italy and occupied the country’s northern region before anything could actually happen. The two final years of the war were a trying time for Italians living in an occupied country—once an ally, now an enemy. Rome, Open City by Rossellini is the only movie to have successfully depicted the resistance to Nazi control.

The first book in his war trilogy relates the tale of the Italian resistance effort, but Rome itself takes centre stage rather than the people who live here. The city remains motionless and confronts the present and the states that will exist long after all the inhabitants have disappeared despite all the violence, destruction, and inhumanity. Rossellini uses a documentary-style method to make a powerful movie that is a monument to life triumphing over death and a ferocious cry against the dreadful evils of war.

Shoeshine

Another children’s story, Shoeshine, tells the sorrowful narrative of two shoe shine lads who work near a racetrack and wish they could own a horse. The movie explores the challenging circumstances that many young people encountered after the war, forcing them to engage in unlawful activities in order to survive. Vittorio De Sica expertly directs a heartbreaking tale that focuses more on the appalling conditions of Italy’s prison system than on the criminal life and the people who fall into it.

Stromboli

Ingrid Bergman wrote Roberto Rossellini a letter in 1950 expressing her respect for his work and wish to collaborate on a film. The connection that developed led to some of the greatest movies of all time, including Stromboli, and one of the most contentious love affairs in the history of cinema.

Bergman portrays a Lithuanian immigrant in an Italian prison camp in the movie. In order to be set free and later transported to his home island of Stromboli, she marries an Italian man she does not adore. She discovers that the people in this remote area reject and alienate her, and she is forced to overcome her phobia of living on a volcanic island in order to survive.

The Earth Trembles

Even though Luchino Visconti is best renowned for his historical epics like The Leopard and Ludwig, one of his earlier works is a lengthy depiction of the struggles experienced by those who are most in need. The narrative of Sicilian fishermen is followed in The Earth Trembles, particularly that of a family who decides to create their own business and evict wholesalers. Visconti’s film is about three hours lengthy and permits editing to depict daily life in detail, leaving no conflict unresolved. This forces the audience to comprehend the suffering, difficulty, beauty, and complexity of existence on the periphery of society.

The realistic technique bridges the gap between truth and fiction by using actual fishermen in both scripted and unscripted sequences. The Italian Communist Party initially requested a documentary from Visconti, who used the money to do something much larger than a propaganda piece. Visconti imagined and realised a gloomy, grim, yet humane and beautiful, expression of unity and empathy.

Umberto D

One of Vittoria De Sica’s most well-known movies is a profoundly humanistic examination of survival and mortality. Umberto D is the tale of an elderly guy who might be kicked out of his home. Umberto realises that time is running short and that he must do all it takes to cling on to his life and to the fleeting beauty of life as he strives to acquire the money. Carlo Battisti gives a powerful performance in his first and only acting role in this terribly sad and cruel film, which is also magnificent and poetic. De Sica is at his best in this film.