One of the most eagerly awaited horror movies of 2023 is Ari Aster’s Beau Is Afraid, which has an April 21st release date. The film, which is being marketed as a type of “nightmare comedy” and stars Joaquin Phoenix, is expected to be purposefully obtuse in narrative and more surreal than anything we’ve ever seen from Aster. Many people are already delightfully perplexed about the specifics of what will happen in this odd trip based solely on the movie’s teaser. The story of generational pain told in Beau’s poster is unsettling and ethereal, following the protagonist through four hallucinatory phases of his life. Beau Is Afraid is probably Aster’s most epic film to date, yet it still has all the hallmarks that have made his associations with A24 so happy-chance. Here are some movies to keep you in the mood for Beau as we eagerly anticipate the springtime premiere. These movies either directly inspired Beau or have continued to have a significant impact on Aster’s oeuvre.

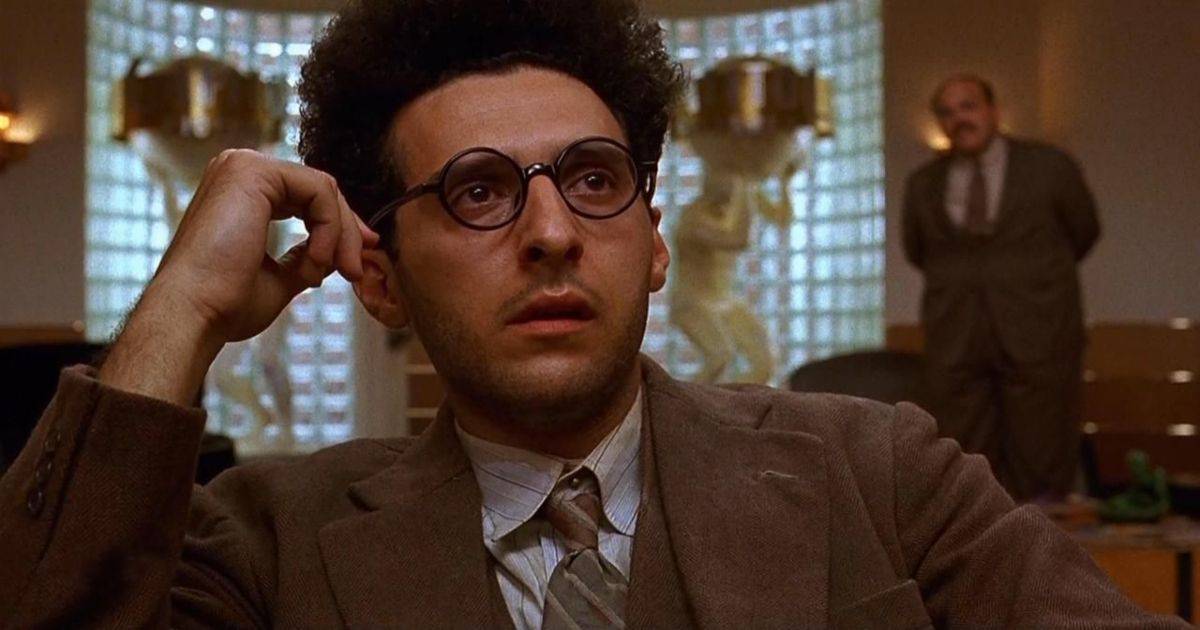

Barton Fink (1991)

There is more than meets the eye when comparing Aster with the Coen brothers. They are all experts in the “interior of the mind,” though in very different ways. What does it take to actually drive someone to their breaking point? Is it really feasible to make a difference in this world? While these themes permeate every Coens film, they also serve as the inspiration for the filmmakers’ charming brand of absurdist humour that occasionally borders on nihilism. Many people have characterised Aster’s most recent work as a comedy, so it would not be surprising if the journeys he leads us on have a Coen-like quality.

I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020)

I’m Thinking of Ending Things may not be a conventional “horror” film, but it has the same eerie, paranoid vibe that permeates all Aster movies. Fans have expressed confusion about what exactly is “going on” in the plot of Beau is Afraid despite Charlie Kaufman’s reputation for producing movies with incredibly abstract plots. There have been many different hypotheses put up over the years regarding the subject matter and point of view of Kaufman’s movie, and if there is one thing we can say with certainty about Beau is Afraid, it is that it will undoubtedly spark similar debates. Throughout the movie, Joaquin Phoenix ages dramatically; the trailer alternates between showing him as a growing youngster and a senile old man. It will be difficult to distinguish illusion or delusion from reality, just like in Kaufman’s time-traveling movie.

Midsommar (2019)

The influence of Aster’s two major motion pictures, Midsommar and Hereditary, on the horror genre during the previous five years cannot be overstated. Both are highly unique, eccentric depictions of A24-sponsored fear, but Midsommar seems to top them both in terms of pure psychological unease, especially as we witness its characters fall apart over the course of the film. With Beau is Afraid, Aster takes psychological dread one step further away from traditional horror clichés and toward a more contemplative, character-driven style. Midsommar would undoubtedly be the one of his movies to have either of these traits, not to mention its profoundly dream-like aesthetics, which are more than apparent in Beau’s trailer.

Mulholland Drive (2001)

Mulholland Drive by David Lynch has a truly unpleasant quality that is concealed beneath its captivating shine. For Lynch, it is saying a lot because the 2001 classic is one of the director’s most daring and broadly appealing works. For those who have seen the movie—spoiler alert for those who haven’t—it is an absolute necessity when it comes to “dream” cinema, or films that explore the nature of dreams while also challenging the foundations of reality. These topics will be examined in Beau Is Afraid as they relate to loss and a family’s history over time, and it will be fascinating to contrast Lynch’s and Aster’s dream interpretations.

Persona (1966)

Aster is no new to the time-defying impact of Ingmar Bergman, like his many predecessors. It is easy to see how Bergman’s spirit remains in every Aster movie given that he lists this one as his personal favourite and number one on his Criterion top ten list. The way the movie “adopts a dream-logic in a truly forward-thinking way” is something he specifically notes. How will Aster continue to both follow and refute this reasoning with Beau is Afraid? The most crucial concerns are all raised by Bergman’s psychological nightmare concerning the gradual emotional “convergence” of two women, and Beau Is Afraid may provide an answer while posing a number of new ones. Aster’s work, within the context of contemporary horror films, continues to push the envelope of how Persona is deserving of its reputation as one of the most cerebral films of all time.

Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Yes, Rosemary’s Baby may be one of those gruesome movies that is okay to see again after dark. It’s not difficult to see how directly the movie influenced Aster’s debut feature, Hereditary; on the surface, both movies deal with the occult, but more specifically, how tragedy can gradually split families apart. Similar themes will be explored in Beau Is Afraid on a much broader scale, and it will be interesting to watch how Aster adapts Rosemary’s Baby in a more surrealist way. All of this demonstrates how, despite their seeming differences, Aster’s movies are all replete with overarching symbolism that unifies them and makes them always accessible for interpretation.

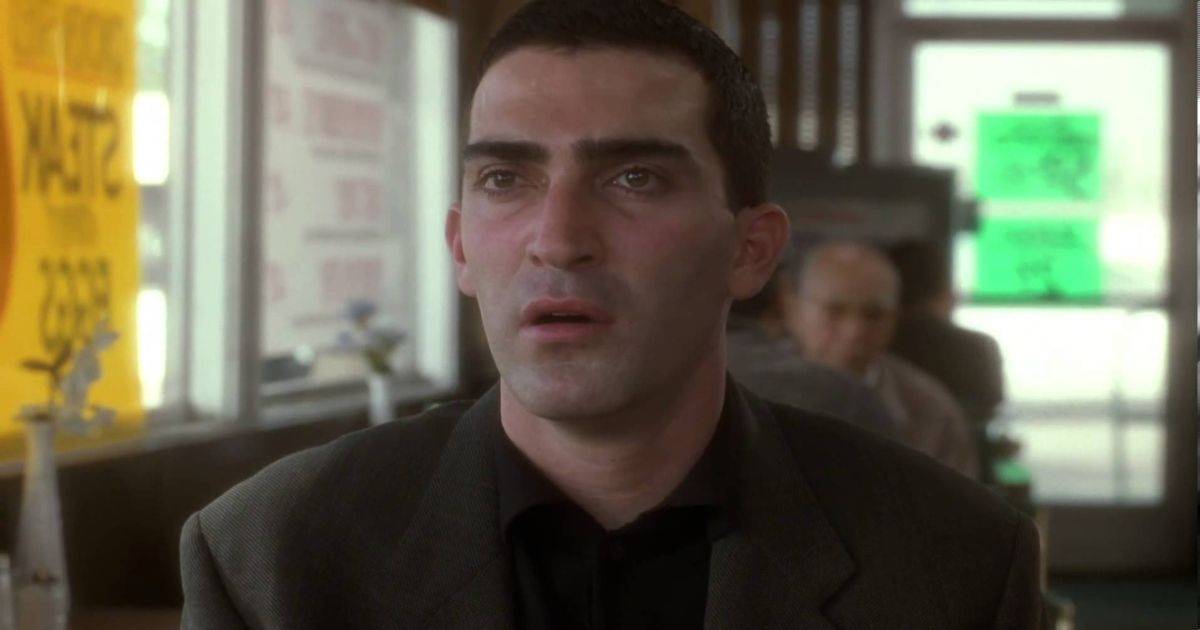

Synecdoche, New York (2008)

Mr. Kaufman is without a doubt the director who deserves to be listed twice on this list. I’m Thinking of Ending Things may be one of Kaufman’s most cerebral works, but Synecdoche, New York is his true masterpiece, and it appears that Aster is aiming for one as well. Synecdoche, New York, which centres on a melancholy theatre director (played by the late, great Philip Seymour Hoffman), also blurs the boundaries between “reality” and fiction, but this time using the idea of character development. The theatrical atmosphere that permeates Beau Is Afraid is definitely inspired by Kaufman and Hoffman’s lived-in world of play sets. The several sets have a dreamlike quality, but they are also oddly two-dimensional, which makes them even more unsettling.

The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989)

the British author The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover by Peter Greenaway is a masterwork of decadence and depravity that will undoubtedly endure through the ages. Similar to Aster’s oeuvre, the movie is not so much propelled by storyline alone—it follows a straightforward vengeance story—but rather by extravagant aesthetics and character complexity. Aster has consistently praised the movie, calling it “pure evil”—which is undoubtedly a compliment in this instance. But what genuinely distinguishes Greenaway’s and Aster’s films is that they are much more than mere diversions in the arts. The enduring themes in these artists’ works are beyond bounds, with Greenaway’s being a blatantly political indictment of fascist persecution.