When it comes to performers in their later years, Russell Crowe stands out for his flexibility. The Australian actor, who made his name as a leading man in the beginning, has easily transitioned into supporting roles in recent years. In Showtime’s “The Loudest Voice,” he just made the switch to television in the role of Fox News founder Roger Ailes. He also recently made his directorial debut with the World War I epic “The Water Diviner.” He may have received some of his harshest critiques ever for his outrageous portrayal in the 2020 road rage thriller “Unhinged,” but it nonetheless demonstrated a refreshing willingness to try new things.

It is difficult to choose out Crowe’s best work. He has also produced historical dramas, romantic comedies, motivational sports movies, grimy crime thrillers, and everything in between. He is not only the star of two back-to-back best picture winners, one of which also garnered him a best actor award. Because there isn’t just one kind of Russell Crowe movie, his filmography is diverse. Here are his top 13 films, listed from best to worst, keeping that in mind.

3:10 to Yuma

James Mangold’s remake of the classic western “3:10 to Yuma” is a remake deserving of the original, much like “State of Play.” Crowe assumes the part of infamous gunslinger Ben Wade, which was first played by Glenn Ford in the 1957 movie, to depict what occurs after Wade is apprehended by a modest rancher (Christian Bale), only to team up with him as they elude Wade’s men on their way to the title railroad stop.

Crowe and Bale modernise stereotyped Western characters in “3:10 to Yuma.” Bale gives the movie the weary air of a wounded warrior, and Crowe depicts Wade as a byproduct of his surroundings. His atrocities are the result of an unfair government’s failure to distribute resources quickly enough, which allowed a criminal cult to grow. Instead of playing a cartoonish villain, Crowe plays a pragmatist who has carefully built his reputation.

Early on, Crowe’s leadership of his men—particularly his top lieutenant Charlie Prince (Ben Foster)—is demonstrated, and the gang’s unwavering loyalty to Wade creates the setting for an intriguing conflict when the outlaw comes to the rancher and his son’s defence. Even though it copies some of the original’s essential beats, “3:10 to Yuma” from 2007 is a stand-alone Western masterpiece.

A Beautiful Mind

“A Beautiful Mind,” the second of director Cameron Crowe’s back-to-back best picture awards, methodically explores the turbulent life of brilliant mathematician John Nash. As the neurotic genius is initially distinguished by his social awkwardness and later by his schizophrenia, Crowe once again demonstrates his ability to depict stern people with depth and humanity.

Respectfully, Crowe refrains from engaging in gaudy oddities that would minimise or diminish Nash’s problems. Instead, “A Beautiful Mind” effectively addresses mental health trauma, eschewing damaging preconceptions. We observe Nash’s fall via his own eyes; the audience also experiences a surprise when Nash learns that he is experiencing delusions because we were lead to believe that Nash’s view was true. The entire narrative is wonderfully told from Nash’s point of view by director Ron Howard, who also elaborates on the signs and symptoms of his condition.

The picture is guided through story beats that can feel like biopic clichés by Crowe’s honesty. The relationship between Nash and his protégé Alicia (Jennifer Connolly), who later became his wife, comes across as touching rather than forced, and the classic “inspirational end speech” in which Nash refers to Alicia’s love as his anchor point, is genuinely moving. Compared to other best picture winners, “A Beautiful Mind” feels weak, but Crowe’s performance is still exceptional.

American Gangster

“American Gangster,” another collaboration with Ridley Scott, is a 157-minute epic cat-and-mouse game that never loses its interest. Crowe plays Richie Roberts, a Newark investigator and aspiring attorney who develops an obsession with Frank Lucas, the head of the Harlem mob (Denzel Washington), and his ascent to notoriety as the rare Black mobster.

In order to allow Washington’s tremendous magnetism to shine, Crowe, who has the task of portraying a man who is entirely overpowered by Lucas’ power, appropriately mutes his on-screen presence. Robert is perplexed by “the Black Godfather’s” success in a generally racist town, and his frustration is increased when his fellow law enforcement personnel reject his well-informed observations.

Roberts and his ex-wife (Carla Gugino) fight in a side story during the divorce procedures, which adds to the idea that Roberts is overburdened. A movie like this needs two explosive protagonists, and happily, Crowe and Washington are just as good as you’d expect. It’s remarkable to watch the respect that emerges between Robert and Lucas, two hardworking professionals on different sides of the law.

Body of Lies

In Ridley Scott’s spy thriller “Body of Lies,” Warner Brothers Crowe plays one side of a remarkable buddy team. Leonardo DiCaprio plays field officer Roger Ferris, who is aided by Crowe’s character, CIA chief Ed Hoffman, on a perilous operation to infiltrate a terrorist group in Jordan. Hoffman is typically loyal and follows the rules, but when he learns that the US government is deliberately disseminating false information, Ferris’ rebellious spirit starts to rub off on him.

Crowe spends much of his time on the sidelines, supervising activities from a base, while DiCaprio is right in the middle of the action. As Hoffman is forced to make difficult decisions, Crowe plays on his fears for him while fighting off the strong powers who want to silence anyone who divulges the secrets of the government. As a result, Crowe’s realistic scenes are just as thrilling as DiCaprio’s action-heavy ones.

Hoffman is so preoccupied with the details of the statistics that he frequently takes for granted the hazards Ferris faces, so Crowe adds just the right amount of humour to the mix. Despite the fact that the two leads hardly ever appear together on screen, their connection is thoroughly developed. Although “Body of Lies” is an underappreciated movie, neither Crowe nor Scott should be viewed as having made a lesser effort.

Boy Erased

Crowe’s willingness to take on smaller jobs and make the most of his short on-screen time is one of his most impressive traits. A good example is “Boy Erased.” Crowe gives depth to a role that might initially seem one-note as a respected auto dealer and Baptist preacher who sends his gay son Jared (Lucas Hedges) to conversion treatment, subtly complementing the younger actors at the movie’s core.

The examination of these horrifying camps is started by Jared’s father’s actions, but Crowe’s character is more nuanced because he doesn’t openly hate his kid. He is motivated by misdirected empathy, which sets up a complex father-son argument once Crowe sees the suffering his child has gone through. It’s a smart performance that never seems to be supporting discrimination or to take Jared’s pain for granted.

When Nicole Kidman tries to gain more agency, Crowe complements her on-screen by making subtle but potent threats. Similar manners characterise his final encounter with Hedges, as Jared’s father offers words of gratitude that seem hollow in light of his refusal to apologise. While not the main focus of the movie, Crowe elevates “Boy Erased.”

Cinderella Man

Boxing dramas are timeless, and “Cinderella Man” by Ron Howard is one of the best in recent memory. James J. Braddock, a mild-mannered light heavyweight who returns from injury to compete for a title opportunity, is portrayed by Crowe in the film. Braddock had previously given up the sport because he felt it burdened his wife Mae (Renee Zellweger) and their little son Jay (Connor Price). Joe Gould, a longtime friend and Braddock’s trainer, only persuades Braddock to make a comeback (Paul Giamatti).

In a masterful performance, Crowe portrays a character who unexpectedly serves as an inspiration to his New Jersey neighbourhood during the Depression. Crowe maintains his modesty even as Braddock moves on to the next round. In a heartwarming scene, Braddock has Joe repent for stealing, displaying his role as a strict yet loving father.

While “Cinderella Man” is unwavering in its authenticity, its combat is savage. Crowe reshaped himself physically and made the boxing sequences thrilling. By the end of Braddock’s title match, it becomes obvious why his tenacity served as an example to so many during a time when there wasn’t much hope.

Gladiator

One of the essential cinematic epics of the twenty-first century, “Gladiator,” is where Crowe won the Academy Award for best actor. Maximus Decimus Meridius, a modest Roman general who is promised the title of Emperor by the current ruler, Marcus Aurelius (Richard Harris), is given all the dramatic potential by Crowe. This act prompts Marcus’ vengeful son Commandus (Joaquin Phoenix) to murder Maximus’ family and sell him into slavery. Maximus must advance through the ranks of gladiatorial warfare, as the title suggests, in order to uphold the law.

When done so skillfully, a traditional approach to a well-known theme of grief and retribution is anything but stale. Crowe keeps the action emotionally real despite the grandiose grandeur of Ridley Scott’s thrilling action sequences because his loss motivates him to play the violent games. Maximus is used to noble warfare, not the filthy, intimate savagery of gladiators, thus Crowe portrays his unfamiliarity with this form of combat brilliantly.

Phoenix’s snivelling performance simply heightens the tension before the pivotal last combat because the grief of Maximus’s loss is never forgotten. With Crowe as its core, “Gladiator” is more than the sum of its parts; the intricate historical setting and subtle language aren’t a hindrance to moments of both triumph and tragedy.

L.A. Confidential

“L.A. Confidential” is still a tonne of fun, even though it takes a more sombre approach to a noir story set in Los Angeles than “The Nice Guys.” Through this examination of police violence and the nuanced performances by Crowe as the abrasive LAPD officer Bud White and Guy Pearce as the nerdy analyst Ed Exley, the nostalgic approach to film noir is modernised.

The combination of these contrasting personalities lends itself to some humour, but “L.A. Confidential” takes its investigation into the blackmailing of well-known Hollywood people rather straight. It puts more pressure on Pearce to control Crowe when he has unexpected and violent outbursts, especially during the opening recreation of “Bloody Sunday” in the movie. The characters are so duty-driven that they rarely express their affection for one another, yet a bright spot emerges at the ambiguous conclusion that suggests that corruption will persist despite their best efforts.

Kim Basinger earned an Academy Award for her portrayal of upscale prostitute Lynn Bracker, and their romance updates the clichéd pairing of the femme fatale and the brooding investigator while giving both characters a sense of agency. One of the noir tropes subverted in “L.A. Confidential” is Crowe’s emotionally stunted rule-breaker.

Master and Commander: Far Side of the World

There is a reason why “Master and Commander: Far Side of the World” fans continue to demand a sequel nearly twenty years after the film’s debut. The Napoleonic epic may not have performed well at the box office, but Crowe’s portrayal of literary hero Jack Aubrey is a major factor in why the movie has remained a fan favourite. It is also one of the most precise and tense depictions of naval action to ever appear on screen.

The HMS Surprise’s commander is a well-respected wartime veteran, but due to his escapades, Aubrey is exposed to dangerous weather and missions to catch French privateers. Crowe has a fun rapport with his team, whom he expresses affection for yet keeps at a remove out of respect for their work. Aubrey has witnessed men he cares about perish in battle, and the loss of even a single crew member breaks his heart.

The team makes every fighting decision despite the epic scope of Peter Weir’s enormous sets and ear-splitting action sequences. During these tumultuous episodes, Crowe’s titular character is tasked with giving guidance and inspiration. Even though it’s unfortunate that “Master and Commander: Far Side of the World” didn’t lead to a continuing franchise, it is still Russell Crowe’s greatest professional success to date.

Romper Stomper

Given that his breakthrough performance was as a very unlikable character, it’s amazing that Crowe has found success as a captivating lead. Crowe played a brutal neo-Nazi who leads a violent skinhead gang into clashes with rival gangs in the 1992 Australian movie “Romper Stomper.” With his propensity for sociopathic conduct and unprovoked outbursts of hostility, Crowe is frightening in this movie.

Crowe portrays Hando as a cocky bully who is shocked by the increase of diversity in his neighbourhood. Although there is no attempt to humanise him, he is horrifying, and Crowe’s reality elevates the ensemble, which does include a few characters who undergo growth and change. Nevertheless, “Romper Stomper” is frequently tough to watch due to Crowe’s skillful portrayal of the white supremacist.

Although “Romper Stomper” has flaws and overuses “Reservoir Dogs”-style embellishments, Crowe elevates the material, particularly when Hando’s fears are put to the test in the final act. “Romper Stomper” is interesting mostly because you can see Crowe redeem a film that wouldn’t be nearly as exciting without him. Crowe would go on to star in fantastic films from respected directors.

State of Play

In the film adaptation of the popular BBC limited series “State of Play,” Crowe successfully recreated journalist Cal McCaffrey. Crowe has no reservations about assuming the roles of iconic personalities. Cal becomes attracted by the mysterious death of Congressman Stephen Collins’ (Ben Affleck) teenage mistress because he is an optimist in a society of cynics.

Even if he worries that his influence won’t be significant, Crowe represents the inquisitiveness of a career writer who is motivated to seek justice. Cal is dubious of Collins’ intentions, but he is open to hearing the politician’s explanation. Crowe doesn’t make Cal so pessimistic that the viewer loses pity for him, and McCaffrey’s connection with his protégé Della Frye (Rachel McAdams) is intriguing, allowing McCaffrey to demonstrate his skills while revealing the human side of the restrained character. The American adaptation of “State of Play,” which stars Crowe in the lead role, is a respectable complement to the original British version.

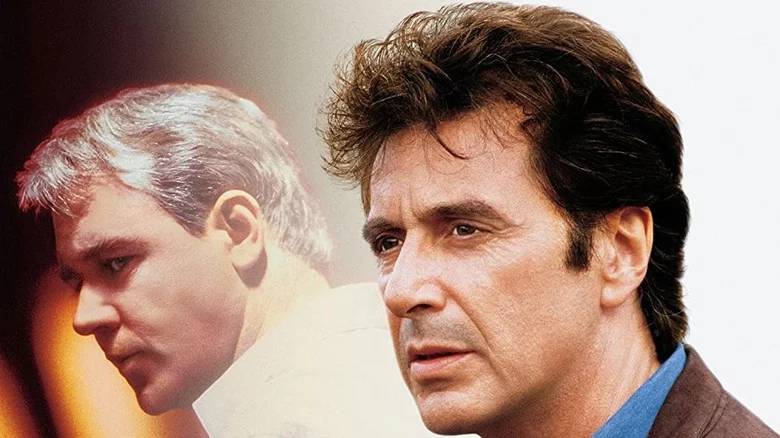

The Insider

For his portrayal of whistleblower Dr. Jeffrey Wigand in Michael Mann’s suspenseful conspiracy thriller “The Insider,” Crowe received his first nomination for an Academy Award for best actor. Leading tobacco industry expert Wigand is reluctantly persuaded to divulge harmful evidence to “60 Minutes” reporter Lowell Bergman (Al Pacino). His life is thus turned upside down as a result of the nefarious operatives working for his former employers spying on him.

Wigand is first extremely worried by Big Tobacco’s denial of the health concerns associated with its products and the association of the sector with governmental organisations, but his concern for upsetting his family life overcomes any desire for justice. It is more compelling to see a reluctant hero struggle with the repercussions of his actions than a hero who is blatantly brave.

For the role, Crowe ditches his typically assured demeanour and gives a portrayal that emphasises the neuroses and anti-social tendencies of the character. When Wigand’s fatherly duties are interrupted by spies and analyzers, it is all the more terrifying because of how those duties are portrayed. Crowe embodies the paranoid, high-stakes world of “The Insider,” a precise, tense thriller.

The Nice Guys

Crowe is underappreciated for his ability to be hilarious. He makes the ideal straight man in comedies thanks to the brutal steadfastness he brings to tragic performances. The Nice Guys by Shane Black, a remarkably underappreciated buddy cop movie, is the best example of this. Crowe plays the intimidating Jackson Healy, a damaged cop who reluctantly teams up with Holland March, an alcoholic private investigator, in the film (Ryan Gosling).

Crowe is ideal as Gosling’s deathly serious counterpoint, swinging for the fences with a crazy performance that aims for Buster Keaton-level physical humour. Crowe is dry enough to suck all the vigour out of Black’s passion, even if Gosling delivers Black’s smart lines in the most outlandish manner conceivable. Crowe’s physicality also sets him apart from Gosling, who consistently manages to harm himself in comically brutal ways.

When conversing with Holland’s daughter, Holly, Crowe exhibits true depth in the performances, which avoid becoming caricatures (Angourie Rice). Crowe makes these moments heartfelt without being overly sentimental, and watching the group work together to solve the case adds to its allure. It’s a real tragedy that the movie’s weak box office performance dimmed Crowe and Gosling’s chances of reprising these roles in prequels.