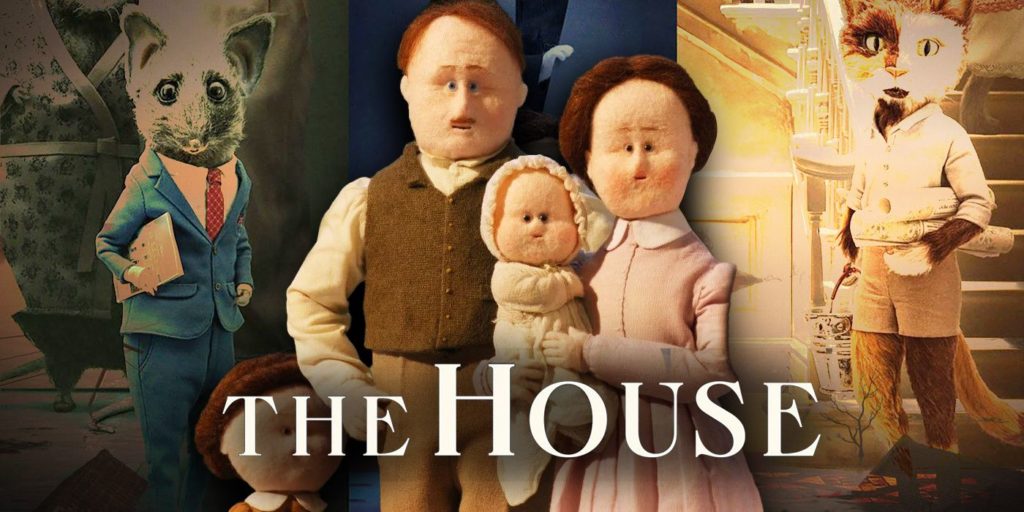

The House, a recent stop-motion animated film from Netflix, told three spooky stories about the same house that ended with few or no clear conclusions, leading many viewers to speculate on the possible meaning. The film, which also features Matthew Goode from Downton Abbey and Helena Bonham Carter from Harry Potter, promises top-notch performance in addition to its beautiful graphics.

The last story is a shining example of letting go of those anxieties and accepting loved ones as your “home,” whereas the other two were warning tales about putting stock in luxury and material ownership out of insecurity. From start to finish, the movie makes overt and covert nods to this idea, drawing the audience in with eerie visuals and dark comedy.

Ⅰ:“And heard within, a lie is spun.”

We are transported back in time and find a four-person family getting ready for the arrival of their affluent and, to be honest, unwelcoming relatives. The basic pleasures of our main characters’ household, such as the gender of their newest kid and the hand-sewn goods made by mother and wife, Penny, are all met with grimaces and turned up noses (Claudie Blakley). Mabel (Mia Goth), their eldest child, navigates their presence with a sense of naïve uncertainty. She believes her house to be more than suitable because her beloved family resides there. In contrast, her father Raymond (Matthew Goode) appears to be quite unhappy with this home and his personal development as a result of several harsh comparisons to his late drunken father made by their guests. Their downfall ultimately results from this insecurity and underlying desire to succeed monetarily since it makes him vulnerable to the exploitation that invariably follows.

For Raymond, having a loving family and a home big enough to accommodate them all comfortably isn’t enough. He needs the external validation that comes with luxury and discovers it in a deal that seems too good to be true. His family accepts the offer from the enigmatic man in the night because of the desperation that drives him, who promises them material possessions beyond their wildest dreams at (apparently) no cost. The only catch is that they are not allowed to go back to their residence; instead, they are only allowed to stay there. This repeating language serves a purpose throughout the short and hints subtly at the larger significance of the forthcoming unusual happenings.

In the story’s concluding scenes, both parents can be seen wholly engrossed in the new way of life this house has given them. When Mable and Isabel get close to their parents, they discover that they have turned into actual pieces of furniture: their mother into drapes and their father into a chair. Reduced to their own selfish material goals, they are allowed to burn along with the house when it catches fire. In a desperate attempt to protect what matters, they manage to assist their children in escaping, but their poor choices and misguided intentions almost certainly lead to a sad outcome for the defenceless couple who are now left in the snow.

Although there are numerous close-to-supernatural occurrences throughout the short, the overall theme is always extremely human: Without love, a house is just a house. Something much more valuable is a home. It is a lonely pursuit to pursue wealth and social prestige driven by insecurity and a strong need for external approval. What would be left if everything you’ve invested so much worth in burned down? What will remain when you make decisions for the people you love?

In keeping with this idea, the first installation in The House seeks to show how easily one may be duped in the quest of happiness through material possession and how fast this goal can contaminate what is actually important in life. The house itself, the enigmatic architect, and the “host” all raised numerous warning flags, but both parents were more than prepared to ignore them in order to realise their misguided ideas of success, even at the risk of their children.

Ⅱ:“Then lost is truth that can’t be won.”

The second section takes place in the present and centres on an anthropomorphic rat that is remodelling the foundation of the first story’s house. He rapidly reveals that he is deeply in debt and is scrimping and saving to finish his project completely at the lowest cost, with the extra pressure of a recession that has been reported in the news.

He battles an insect infestation in the house that worsens over the course of the short, which serves as a powerful metaphor for his gradually deteriorating mental health caused by material-driven wants that go unsatisfied. The fact that the developer (Jarvis Cocker) is never given a name is evidence of his loneliness, which has resulted in a total loss of identity. This is reinforced by his deteriorating social skills, which include making everyone at his performance feel uncomfortable despite his best efforts, and by the revelation that the “sweetheart” he’s been contacting is actually his irritated dentist and not a girlfriend.

It’s conceivable that our main character disregarded his concerns about the odd couple in order to make a sale, but it’s even more likely that his pursuit of an opulent future has made him lose the capacity to trust his own judgement. He finds out right away that they do not intend to purchase (or leaving, for that matter). His long-ignored mental health concerns are becoming more pronounced as the insect and visitor infestation grows, and his pathetic attempts to drive them out only get him admitted to the hospital.

With no purchasers, his loan agency ringing incessantly, and it appearing he has no chance of achieving the goals he has set for himself higher than human connection: The developer had returned to the house and had gone back to his most primitive self. He bids a final farewell to humanity by scratching his ear and ripping off his Bluetooth device before joining the horrible rat-insect hybrids in trashing everything in the house and running into a hole below.

All of these plain cautions stress the significance of the self and connection. What prevents us from degrading to nothing more than animalistic urges in the absence of human connection? If we disregard our most fundamental wants as a route to an aim that could never materialise, what use is life left? What would be left of us to appreciate it if this capitalistic objective is achieved at the expense of self? Once more, the film makes advantage of this depressing conclusion to implore us to realise how fast erroneous priorities in life can result in a horrible end and begs us to place value in what is actually important. Both the founding family and the developer have passed the point of no return, but we may learn from their errors and overcome the pressures of society and the economy that have clouded our own thinking.

Ⅲ:“Listen again and seek the sun.”

It’s very obvious from the title alone that there will be another lesson to be learned, but this time with a different ending that shows how our decisions can stop the previous terrible ends. The House’s third and final instalment brings us into a future in which everything has been submerged by floods except for that same unsettling structure, concluding the cautionary stories.

Rosa (Susan Wokoma), our primary heroine, is the current owner and has had a longtime desire of making the house her home. Rosa’s intention was to utilise her tenants to finance this endeavour and eventually move them out so she could enjoy the fully refurbished home to herself, as we learn during our first seen interaction between the two anthropomorphic cats Rosa and Jen (Helena Bonham Carter). While this goal may be selfish, it is more likely to be incorrect. Rosa has a romanticised image of what “home” is, looking at a picture of her possibly-lost family, but she is blind to the fact that her chosen family has always been there for her. She is unable to recognise that her two renters have remained at her side despite the inevitable desolation because they care for her; she is fixated on an impractical and, once more, materialistic aim.

The ever-present fog pours into the house with the news that the final two are leaving and a final shared lunch with Jen, sending Rosa on a perplexing trip through her memories and emotions. She is given the option to either cherish her history while moving on in the presence of the people she loves or to stay in a solitary delusion that would eventually lead to drowning. Either put a physical structure first or accept the assistance from others around her that she has been oblivious to.

In the end, Rosa realises that a house is not a home and pulls the lever that Cosmos (Paul Kaye) made. With a newly discovered preference for connection above possession, she ventures into the formerly terrifying unknown. She gains knowledge that her forebears in this house lacked, avoids the same terrible fate, and breaks the pattern.

This scene’s conclusion shows us that we all have the ability to choose to be free. The other endings that each character could have attained had they been self-aware enough effectively capture the message that The House wants to convey. Even though we might never have everything we desire and even though it’s simple to get lost in the never-ending quest for financial achievement, the people we spend our lives with are what really matter.

We hear a song during the closing credits that reinforces the message presented in each section:

“How are a house and a home different from one another?

You can never feel lonely at home.

However, a home, oh, a home, is

It’s just a bunch of bricks.

There are numerous quotes in the song’s lyrics that serve as symbols of the importance of human connection and love, which are so frequently overlooked in favour of materialism. The House is a masterful metaphoric film that teaches a valuable lesson from the very first scene to the very last one. It is visually spectacular and loaded with symbolism, which could require several viewings to properly comprehend.