The complicated circumstances surrounding the unexplained murder of Anni Dewani, a 28-year-old Swedish lady of Indian descent, in Khayelitsha, South Africa, in November 2010 are chronicled in Investigation Discovery’s “Anni: The Honeymoon Murder.” The conspirators were swiftly captured by the police, and all of them received sentences or immunity in exchange for their prosecution-mandated testimony against their fellow conspirators in any subsequent court cases. Here is what we currently know about the complex case in case you’re interested in finding out more.

How Did Anni Dewani Die?

On March 12, 1982, Anni Ninna (née Hindocha) Dewani was born in Mariestad, Sweden, to Vinod and Nilam Hindocha. Anni’s father, Vinod Hindocha, was born and raised in Uganda as part of the Indian diaspora after leaving his home state of Gujarat when he was a young man. In 1972, they fled Uganda as a result of President Idi Amin’s order for South Asians to be expelled. After moving to Mariestad, Sweden, Vinod established a business and a life for himself there. He also raised his kids there, stressing the importance of their Gujarati language and Indian identity.

Anni was a young woman with great beauty, charm, and vitality. Though he couldn’t help himself, Vinod pampered his youngest daughter. He got her a new Volvo and a chic one-bedroom flat in Stockholm when she moved there to work in marketing for Ericsson after graduating from college. Vinod even paid the hefty cost when she chose to change her expensive hardwood flooring since she had a preference for a different colour. Nira Hindocha, her cousin, described how Anni “was the glue that held the tightly-knit Hindocha family together” on the programme.

The show claimed that Anni was anxious to help her father, who was willing to support her in her mid-20s hunt for a wife as well as her other pursuits of perfection. She visited London on a regular basis, staying with wealthy relatives because her maternal uncles owned the British drugstore business Waremoss. Her goal was to wed an Indian, and London seemed to provide more opportunities for that than Stockholm did. At gatherings in London, one of Anni’s aunts had noticed Shrien Dewani and was drawn to him because of his excellent looks, wealth, and lineage.

Through a common contact, the aunt obtained his phone number and set up a casual meeting for Anni in a coffee shop. After they clicked, they decided to tie the knot in October 2010. Their lifestyles reflected one another. Like Anni, Shrien came from a Gujarati family with roots in President Amin’s native Uganda and England. Before he turned thirty, he was a millionaire, and on October 19, 2010, two young lovers tied the knot in a lavish wedding that followed Indian traditions and customs in a posh hotel in Mumbai, India.

The couple set out on their honeymoon, travelling to South Africa. After four thrilling days of game-watching in Kruger National Park, they landed at Cape Town International Airport from Johannesburg on November 12 evening. The Dewanis had reserved a stay at the Cape Grace Hotel, one of the priciest tourist destinations in the city, but after a modest dinner on November 13, Anni supposedly wanted to see “the real Africa.” That’s why it was startling when 30-year-old Shrien begged for assistance at 11:30 p.m. to report a hijack to the police.

Shrien said to the police that he and his 28-year-old bride had selected an unusual private township tour, which had gone awry. At approximately 10:45 p.m., two armed guys broke into their car and drove for almost an hour before kicking the driver out and taking Anni with them. After escorting Shrien to his hotel, the authorities began a comprehensive search. The following morning, at around eight in the morning, they found Anni’s body in the backseat of a grey Volkswagen Sharan minivan in Elitha Park, Khayelitsha. Anni had been shot in the neck at close range using a nine-millimeter pistol.

Who Killed Anni Dewani?

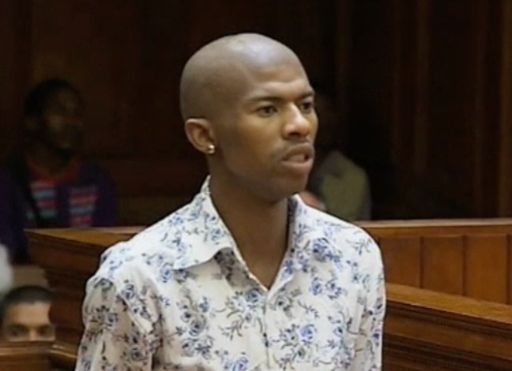

After Anni Dewani’s body was found, forensic specialists from the police department travelled to Khayelitsha. At the murder scene, they discovered a crucial piece of information: a handprint and fingerprint on the left fender of the minivan. They belonged to labourer Xolile Mngeni, who was unemployed at the age of 26. Xolile’s fingerprints were retained in the national police database despite the fact that his previous arrest was withdrawn despite his alleged involvement in the death of a man during a pub fight. On November 16, they found him close to his grandmother’s house in Khayelitsha, not far from the abandoned automobile.

Xolile was taken into custody after being awakened from a night of partying in his shanty with other people. A cell phone that one of the cops discovered wedged between the mattress and bed frame belonged to Zola Robert Tongo, the taxi driver for the Dewani family, according to Xolile’s claims in court papers. Xolile instantly admitted to being involved in the murder, naming Mawewe as an accomplice. While questioning Xolile, the most elite police force in South Africa, the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation, oversaw the search.

On November 18, the authorities discovered the accomplice, Mziwamadoda “Mawewe” Lennox Qwabe, thanks to a tip from a reliable source. He acknowledged his involvement in the crime and divulged more details, including the identity of a second co-conspirator, Monde Mbolombo, the hotel receptionist. The third suspect, Zola, the driver for the Dewanis, was wanted by the police as Anni’s funeral service was taking place in London on November 20. Zola turned himself up to the authorities almost immediately, accompanied by his attorney.

Declaring the Dewanis to be the victims, Xolile admitted to kidnapping, armed robbery, and hijacking. Mziwamadoda changed his story to incriminate Shrien in a premeditated murder after first denying any involvement in these killings. At first, Monde admitted to organising the armed robbery and hijacking, but he afterwards stated that Shrien had requested a premeditated murder. Prior to subsequently claiming that the operation was a premeditated murder carried out by Shrien to appear like a chance hijacking, Zola had also initially claimed to be an innocent victim.

Mziwamadoda and Zola were granted reduced terms under Section 105A of the Criminal Procedure Act in exchange for their guilty pleas, assistance in testifying against Shrien, and other associated criminal procedures. In December 2010, Zola was given an 18-year sentence that was contingent on her giving an honest statement against Shrien in any further court cases. In February 2011, Mziwamadoda received a sentence of 25 years with the same conditions. His attorney said that because of purported police influence during the statement process, a fair trial would be unattainable

.

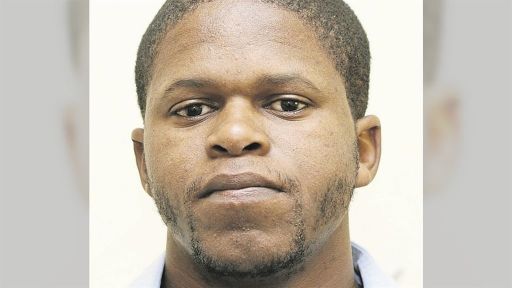

According to Section 204 of the Criminal Procedure Act, Zola Robert Tongo Monde received total immunity from prosecution in exchange for his truthful evidence against Shrien and associated criminal actions. Because of Xolile’s June 2011 brain surgery to remove a tumour, his study was postponed. He entered a not guilty plea in his 2012 trial despite having previously confessed, arguing that he had an alibi and that torture had been used to coerce his confession. The confession was found to be inadmissible, and in November 2012, he was found guilty of murder and given a life sentence.

Following a protracted legal fight, on April 7, 2014, Shrien was deported to South Africa, where he was detained, accused, and given a trial date for allegedly planning Anni’s murder. He entered a not guilty plea to each of the five allegations against him, which included conspiring to commit kidnapping, robbery, murder, kidnapping, and obstructing justice. Important witnesses who had testified against him in October 2014 were discovered to have falsified their testimony. On December 8, 2014, the case was finally dismissed, and he was found not guilty of any of the allegations.