These are some of the qualities of the great epics made by some of the most renowned filmmakers: stories that are larger than life, historical moments permanently immortalised, and some of the greatest feats in the history of motion pictures. The astounding exploits that followed were occasionally praised, criticised, or misinterpreted.

Some have been forgotten or had their importance revised as the years and generations have passed, but the strength of their ambition has proven to stand the test of time. All of these films, from epic ones set in biblical periods to those set in the near future, have a lot to say about what makes humans tick (with a lot to look at, too). The top 20 cinematic epics of all time are listed here.

A Bright Summer Day (1991)

The movie by Edward Yang Not only does A Bright Summer Day deserve a position on any list of epics, but it ought to be near the top. A powerful tale that is at once vast and delicate, enormous and personal, and merciless and kind. A life of transition at one of its most turbulent phases, the best representation of an adolescent wasteland, and the impending abyss of adulthood are all shown in this work.

The life of a little boy growing up in Taiwan in the middle of the 20th century is a monument to both Yang’s country’s complex past and to all generations of children searching for their place in the world.

Andrei Rublev (1966)

Andrei Rublev, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky for Mosfilm, is a reflection on faith and the place of the artist in society. It tells the story of a devout painter (Anatoliy Solonitsyn) and the events that define his life. From his establishment as an artist and floating through a perilous, ill-defined, yet Russian region to his eventual retreat from his practise and return to religion and art.

Andrei Rublev is a spectacular monument to religion and to people who resist persecution and a brilliant affirmation of the function of art in life (at its time censored by the atheist Soviet government).

Apocalypse Now (1979)

Apocalypse Now, which is an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, is flawed, convoluted, and yet yet completely beautiful. It is a journey into profound darkness. The follow-up to Francis Ford Coppola’s early and mid-’70s hits is a surreal exploration of the Vietnam War and the shattered minds it resulted in.

Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), who has gone rogue and is reputedly insane, is fighting the Viet-Cong with a guerilla force that views him as a demigod. Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) is assigned to kill Colonel Kurtz. There is more to the story than Willard has been given as the tale develops. Through his eyes and conflicted motivations, he makes Vietnam appear more like a mental hospital than a battleground—a place where men are sent to die and discover the darkness of life within themselves.

Barry Lyndon (1975)

In general, it’s filmmaker Stanley Kubrick’s odd geniality at making the most of the part chance can play in the evolution of life. It’s that conspiracy theory, that ground-breaking camera technique, that emotional detachment in its depiction, but mostly it’s that. His most underappreciated film, Barry Lyndon, may also be the one that has held up the best over time thanks to its exquisite and distinctive technical aspects.

The movie’s excellent acting, led by Ryan O’Neal’s sly and uncanny portrayal as the title character, underlines its grandeur despite the fact that it is beautifully slow-paced but never feels that way.

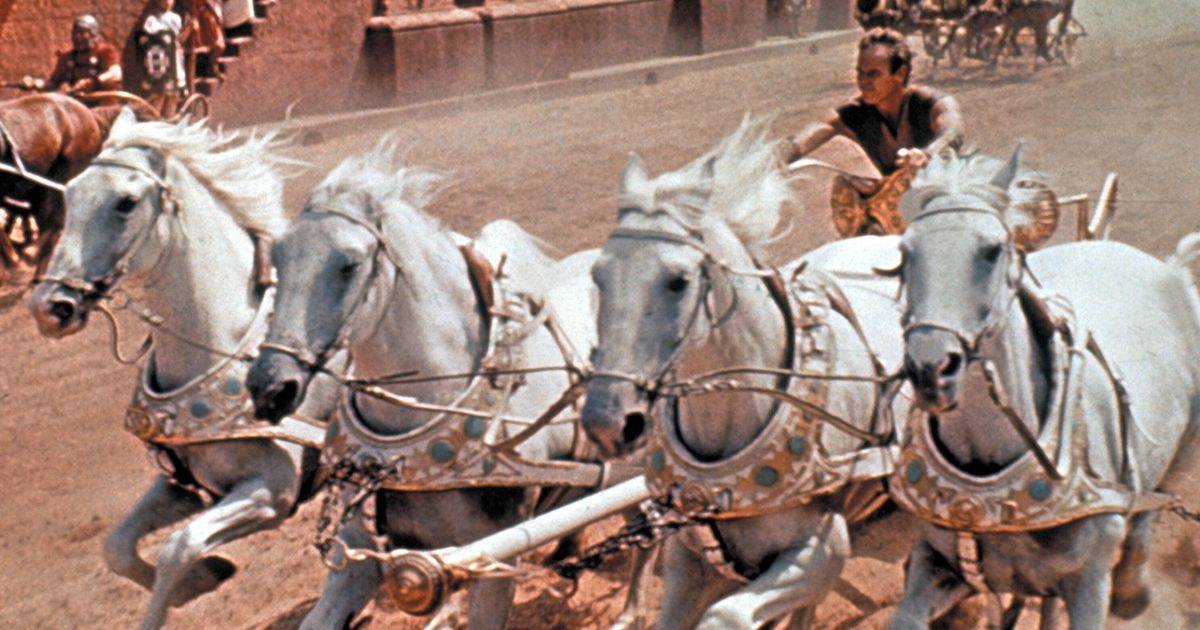

Ben-Hur (1959)

Charlton Heston plays Judah Ben-Hur, a Jewish aristocrat deceived by his Roman friend, who is imprisoned on a prison boat and has his family sold into slavery in this epic religious drama set at the time of Christ. An experience with Jesus transforms his heart and outlook on life after his escape and his thoughts becomes focused on retaliation.

Ben-Hur, which earned millions of dollars and won 11 Academy Awards, is remembered for its iconic images, illustrious performances, and historic chariot races. It changed the face of cinema for decades to come.

Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965)

Doctor Zhivago, an homage to romance amid the difficulties of life, follows the life of a doctor (Omar Sharif) as his existence is irrevocably altered by the Russian Revolution. Although history serves as the judge, juror, and executioner of the characters’ lives, it is these lives that Doctor Zhivago specifically focuses on: their flaws and virtues, their responses to triumph and sorrow, and how the human spirit copes with the unavoidable emptiness of uncertainty and change.

Fanny And Alexander (1982)

In Fanny and Alexander, the great Ingmar Bergman presented brutal and sinister stories in a delicate manner. Even though the darkness is still there, something has changed from his earlier works, which were a dark journey into the human soul. He seems to let go of this in this movie, which was supposed to be his swan song.

Hope still clings, family is still there, love is there to be had, and enchantment is still present in a child’s heart as the siblings at the forefront of the movie struggle to deal with the unhappiness brought on by their mother’s new marriage. In a 312-minute trip of cinematic pleasure, ghosts, telepathy, religion, and imagination come to life.

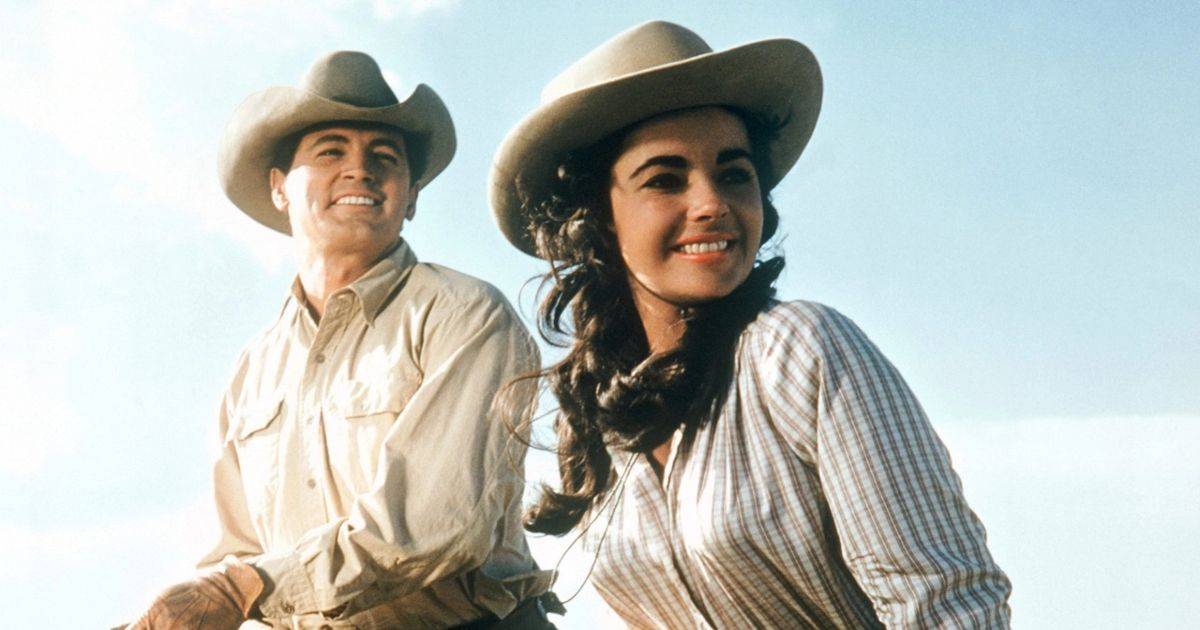

Giant (1956)

Giant, which follows three generations of a wealthy Texas family through decades of upheaval, racial discrimination, and their own struggles, features George Stevens at the peak of his career. Giant is primarily a portrayal of Texas in transition, but it is also a portrait of the American family and how any prejudices that may be held about it will inevitably change. Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor, and James Dean in his final appearance give powerful performances that bring this imposing examination of race, power, and love to life.

Gone with the Wind (1939)

Scarlett O’Hara’s (Vivien Leigh) and Ashley Wilkes’ (Clark Gable) timeless love story has remained relevant over time. This melodrama’s complex relationship, at its core, is marred by jealously, selfishness, loss, and remorse. Through it all, love at a time of war is never meant to be romantically depicted; rather, it is a bond that is destined for and defined by its environment.

Due to its lack of attention on significant societal issues that are present in the plot, Gone with the Wind has undoubtedly not aged as well as many other movies on our list. The work of Selznick is uncritical of slavery and fiercely protective of southern customs.

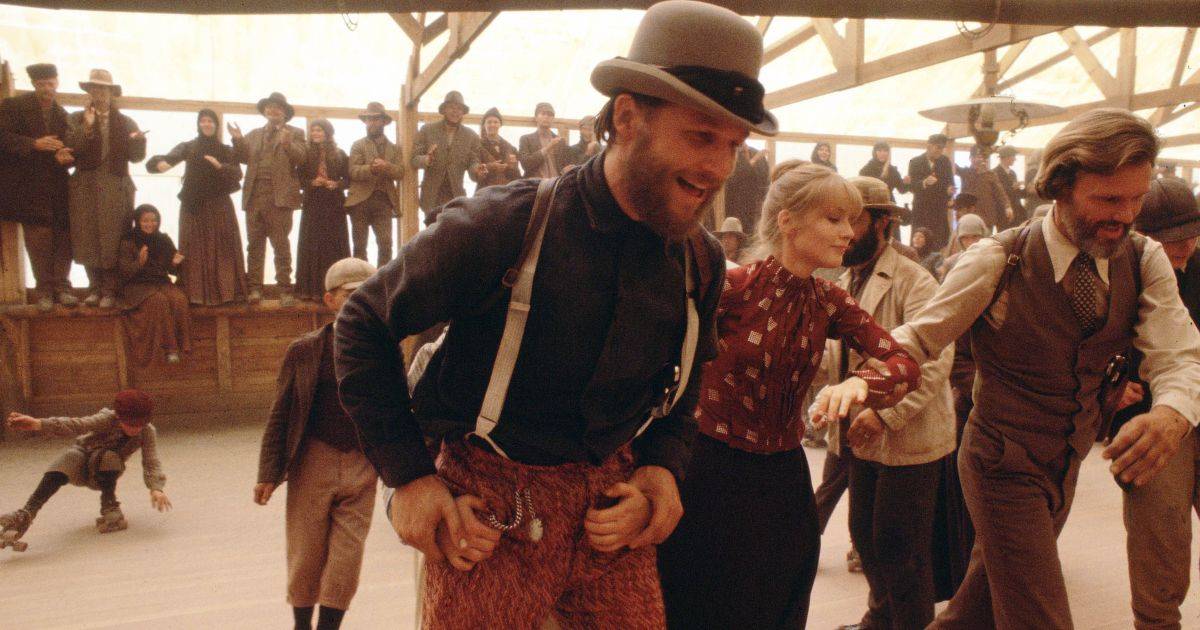

Heaven’s Gate (1980)

The goal for Cimino’s next endeavour, Heaven’s Gate, was to surpass the success of The Deer Hunter. However, a number of obstacles, cost overruns, retakes, Cimino’s purportedly authoritarian directing, and an imposed decrease in the final cut gave the critics a prejudicial attitude.

The movie was pulled from theatres due to negative reviews and low ticket sales, which some claim signalled the end of director-driven movies for the following ten years. A misunderstood Americana masterpiece about prejudice, brutality, and the quickly disappearing past has received new attention in recent years thanks to a new director’s cut and critical reevaluations.

How The West Was Won (1962)

Some movies genuinely live up to their names, while others do so rather literally. Both a massive documentary and a fictionalised account of a pioneer family’s life are featured in How The West Was Won. Given the size of the film, it was directed by three of the top western filmmakers (having John Ford merely handle a small amount of it, what a luxury!). The cast feels so big that it almost feels like it won’t fit on the screen, despite the gorgeous photography and elaborate production design. There is sufficient verifiable evidence to support the claim that John Wayne only appears in one scene.

Intolerance (1916)

Griffith made a movie to disprove his detractors and establish himself as one of the most ambitious artists of all time after The Birth of a Nation garnered harsh criticism for its overtly racist storyline. The end result is the film Intolerance, which weaves together four storylines that are thousands of years apart to explore its title across history.

This motion picture is held in the greatest regard thanks to its spectacular production, enormous sets, and ground-breaking cinematography. Despite being a movie about prejudices throughout history, Griffith’s previous movie glorified the Ku Klux Klan, and he believed that his bigoted critics were the ones who should be ashamed of themselves.

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

What else is there to say about Lawrence of Arabia? influential, recognisable, stunning, and challenging. Its portrayal of moral uncertainty and psychological difficulties was well ahead of its time, elevating David Lean’s epic by cramming in so many subtexts that are both deeply personal and broadly applicable.

The story revolves around T.E. Lawrence’s (Peter O’Toole) life and his support for Arabian independence, but the movie is truly about sexuality, identity, mental health, colonialism, and the never-ending quest for meaning in life. Without Lawrence Of Arabia, there would be no Dune, Star Wars, Spielberg, or George Miller. Lawrence Of Arabia is intended to endure forever.

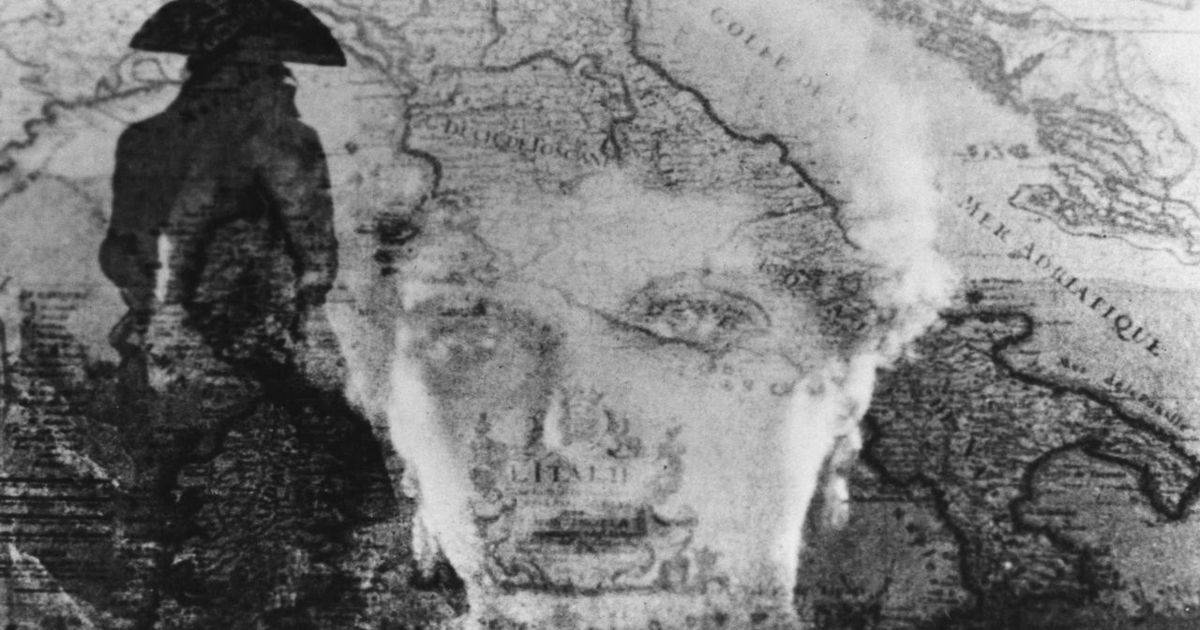

Napoleon (1927)

Only a life so preoccupied with majesty and conquest could provide the plot for one of cinema’s longest, most daring, and avant-garde films. Although Napoleon’s life has been immortalised on film numerous times, Abel Gance’s 1927 work has had a greater influence over time. The best way to define Napoleon is probably as an experiment because it is more than a movie or even an experience.

Here, Gance is more like a scientist than a director; even now, his use of colour, iconography, effects, and sound is totally irrational. However, everything comes together to form a fascinating kaleidoscope of what makes the seventh art so remarkable. The most popular edit of the film covers nearly six hours of Napoleon Bonaparte’s life, from his youth through his invasion of Italy in 1797. Gance intended this to be the first instalment of a six-part series detailing the emperor’s life, but he was never able to secure the necessary funding.

He kept working on Napoleon throughout his life, never arriving at a cut he believed was ideal. Even though numerous versions of the film have been produced since Napoleon’s passing, including those by famous directors and film historians, it may be the most epic movie ever made simply because of the amount of admiration that has inspired so many people to devote so many hours of their lives to studying Napoleon.

Reds (1981)

The second film that Warren Beatty has directed aims high and succeeds. The life of American journalist and politician John Reed is told in the book Reds (Beatty). His dedication to covering the Russian Revolution, American political activism, and his troubled relationship with Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton) are all weaved together with “witness” interviews with significant 20th-century people. As a result, it is an enormous historical drama that is strangely underappreciated.

The expansive plot is supported by a superb cast, as well as a top-notch team (Stephen Sondheim and Vittorio Storaro are responsible for the music and cinematography, respectively). Gene Hackman, Maureen Stapleton, and some Jack Nicholson at the height of his stardom provide supporting roles. In the end, Keaton and Beatty’s outstanding performances as lovers who are enthusiastic about each other and the future are what make Reds so memorable.

Seven Samurai (1954)

a movie that was influenced by later westerns and was inspired by them. It has had such a profound impact on film and culture history that it still permeates daily life. The great conflict between good and evil as shown in the works of visionary and influential director Akira Kurosawa.

A historical narrative of heroes protecting the helpless from the evil, of people banding together to conquer their own challenges, and of finding strength in numbers, Seven Samurai represents the pinnacle of epic cinema. Seven Samurai, one of Kurosawa’s many epics, is considered his best work and a testament to the mystical synthesis of all the components that make up the seventh art.

The Bridge On The River Kwai (1957)

David Lean perfected the epic genre, which William Wyler had created. In the movie The Bridge on the River Kwai, William Holden and Alec Guinness play the leaders of the American and British POWs who were ordered to construct a bridge for the Japanese during World War II. One of them has become proud of his creation and will make an effort to prevent its destruction when preparations to blow it up arise.

The film has a long history as one that illuminates the lives of individuals at war, rather than presenting a good-versus-evil binary. It is well-executed in all respects, poetic, and amusing.

The Leopard (1963)

The central theme of one of the finest movies ever is expressed in Tancredi’s (Alain Delon) remark to his uncle The Prince of Salina (Burt Lancaster): “Things will have to change for them to stay the same.” The Leopard is concerned with change, collective and individual time, birth, death, everything in between, and the inevitable progression (or demise) of everything a person learns throughout a lifetime.

A monstrous movie, directed by Luchino Visconti, was added to his illustrious body of work, documenting the unification of Italy through The Prince’s practical reaction to the social shift in order to guarantee a future for his family. Burt Lancaster’s once-in-a-lifetime performance, in which he personifies the decline of 19th-century aristocracy with sensitivity and humanity, serves as the centrepiece of The Leopard, which is massive in every way.

Until the End of the World (1991)

The length of Warner Bros. Epics has consistently been a problem throughout post-production and release. Studios have placed auteurs in positions where their vision is constrained by business considerations. Sadly, many have undergone significant editing and re-editing by the studios; yet, some of these films are finally published as director’s cuts in all its length and splendour.

This is the case with the sci-fi epic Until The End Of The World by Wim Wenders, which at one point had a 20-hour edit. Two runaway criminals are pursued by the law as they travel the world in search of a strange relic. A nearly five-hour film about change and love has been given the chance to be properly experienced by new audiences thanks to the most recent cut, which was gloriously rereleased through the Criterion Collection.

War and Peace (1966-67)

1956 saw the publication to critical acclaim of an American adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. 1965, and the Soviet Union had just produced their own adaptation of the renowned book as a cultural response. This is not your typical Cold War counterattack; instead, it is a movie that both outperforms and eliminates the American version.

The seven-hour megaproduction directed by Sergey Bondarchuk can only be defined as legendary and unmatched. The movie was well-received by critics and audiences alike, and it continues to be regarded as one of the most remarkable accomplishments in both art history and cinema.