The long-awaited biopic of one of music’s real giants, “Elvis,” made its debut last month to positive, though conflicting, reviews. It was never going to be subtle in Baz Luhrmann’s portrayal of The King, the guy who reinvented rock and roll in the 1950s and became a global phenomenon. His movie is lengthy, densely filled, and uninterested in unimportant topics like realism. Luhrmann saw Presley’s biography as a chance to further delve into his interests in the glitter of fame and the decay that lies behind its rhinestone veneer. This indicates that “Elvis” is noisy, obnoxious, and chock-full of out-of-date musical selections and frantic editing. Everything is flung at the wall over the course of two hours and forty minutes, from groin-thrusting montages to Doja Cat versions of “Hound Dog.”

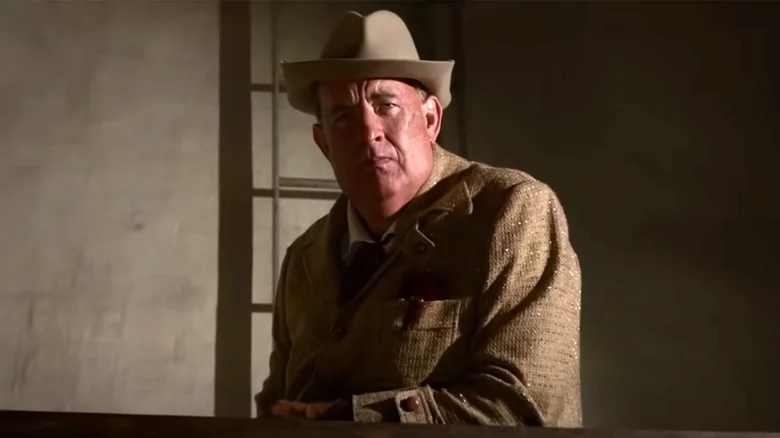

Austin Butler, who portrays Presley astonishingly well, is the eye of the storm. Butler’s magnetism allows us to view the much mocked Presley as a real, breathing human being—the man, not just the myth. Butler brings “Elvis” very close to magnificence, and even the cynical critiques have praised his work. The diverse assessments on “Elvis” have, however, all agreed on one additional aspect: Tom Hanks’ ridiculous performance as Colonel Tom Parker. It’s horrible, according to almost all reviews.

America’s uncle felt like an odd option for the part. He is known for being a kind guy and has generally shunned playing villains throughout his career. Presley’s Svengali manager Parker, who forced him into a protracted cycle of overwork and financial exploitation, was not a kind person. His reputation as the foil to Presley’s epic climb and collapse will live on forever. Knowing this, Luhrmann chose to have the Colonel, an unreliable huckster attempting to rewrite history in his own favour, serve as the narrator of “Elvis.” He is the height of snarling evil, not just a villain. And Hanks does so expertly. Everything for which he is being criticised was specifically requested by the character.

The titular character of the cult British comedy “Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace,” an egotistical hack who writes horror books, makes the following brazen claim: “I know writers who employ subtext and they’re all cowards.” One wonders if Luhrmann and Hanks paid attention to this counsel when making “Elvis.” The narratives that reject stillness in favour of amplifying excess to expose the workings of such theatricalities are used to tell this story, as with all other Luhrmann films, like a fable or an opera. With “Elvis,” we have a fairy-tale with a dashing prince, the temptations of the dark side, and a huge bad wolf, not just a biopic of a renowned musician. The Colonel is cunning, a salesperson who has deliberately eaten his own poisoned apple, in contrast to Butler, who is endearing and gifted but perhaps naive to the brutalities of the world. A careful performance is not necessary for such concepts and framing.

The Colonel’s agenda is set out like that of a Bond villain minutes before he begins firing lasers at 007’s nether regions, in line with Luhrmann’s grandeur and his anti-reality approach to even the most banal of narratives. He aspires to wealth, fame, and immortality in history. Elvis gets hardly any human attention from him at all. When Parker first hears Presley performing, he is informed that the young man singing rock and roll isn’t Black, and his eyes virtually pop out of his skull with dollar signs in his pupils. The listener sees almost instantly the opposite of every assertion the Colonel makes during his narrative, even the Colonel’s own plans. He tries to drain Presley of all of his individual appeal in the cause of profit, only to claim credit when Presley does the complete opposite and receives enormous praise.

The Colonel is determined to have Presley produce a dull Christmas special devoid of anything slightly challenging or fascinating after Presley works behind his back to organise his now-iconic 1968 return spectacular. Hanks’s frightened expression captures the worry that an era of ageing white men in suits losing their ticket to a decent meal is coming to an end as he sees new producers create a colourful, seductive, and completely contemporary show. Many people made a lot of money off of Elvis (much more than the man ever did), and their success hinged on him being a submissive puppet who adopted the fashions they prescribed. The Colonel is the expert on this, despite the fact that he appears hopelessly out of touch with the trends he professes to be so knowledgeable about. The echo of “Shut up and sing” that troubled many a singer over the next decades is Hanks pleading with Elvis to sing “Here Comes Santa Claus” (which he pronounces “Santy Claws,” repeated so many that it stops sounding like a legitimate sentence).

It’s possible that Hanks doesn’t resemble Colonel Tom Parker in real life all that much, or any other actual bad guy in an old-school Hollywood biopic, but that wasn’t the performance Luhrmann was hoping for. His role models are teary-eyed romantics who consider love, art, and the meaning of life. Richard Roxburgh in “Moulin Rouge!” and Bill Hunter in “Strictly Ballroom” are two examples of his literal mustache-twirling villains who youngsters are encouraged to boo at. Even while they don’t feel like real people, their tremendous ruthlessness and elevated goals are very recognisable. It’s not like there aren’t any self-promotional svengalis in the music industry, whose inhumane treatment of their employees is known to all. Luhrmann’s films disclose something all too real amidst the glitz and melody. Hanks’ portrayal may have been a caricature, but what else could it have been?