Cinema, which is largely a visual art form, focuses a lot on the shot and how it is put together. The term “mise en scene,” which is a theatre term, describes pretty much everything that makes it up. The setting, lighting, composition, clothing, and even the placement of the players within the shot all have an impact on the mise en scene, which is pervasive but difficult to define.

When a filmmaker is able to expertly blend all these various visual components of their work into a distinctive whole, the word starts to take on greater meaning. The best examples of such a skillfully designed mise en scene have the power to carry you away. These kinds of films immediately stand out thanks to their distinctive visual style, evocative nature, and excellent fluency in conveying concepts. The top 11 movies for mise en scene are listed below.

Table Of Content

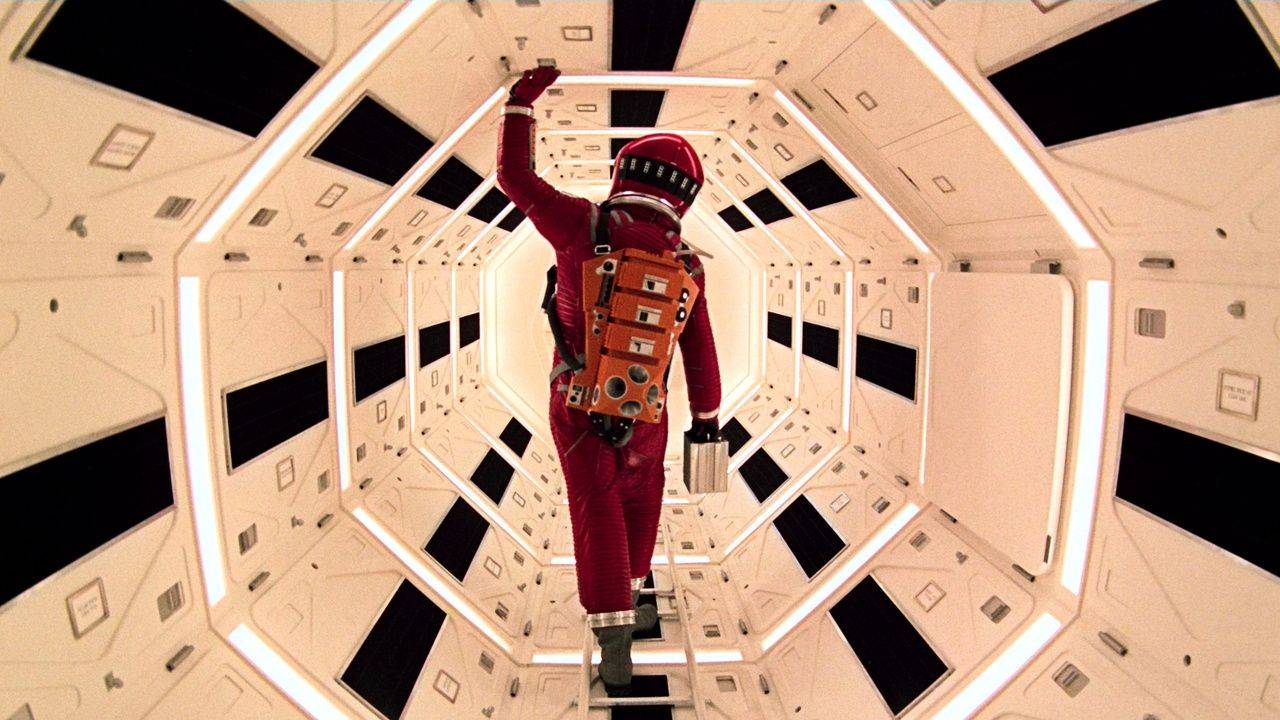

2001: A Space Odyssey

The film that brought Stanley Kubrick the Academy Award for Best Special Visual Effects was 2001: A Space Odyssey. The 1968 film, which had visual effects that were far ahead of their time, even stands its own against modern inventions. The film followed human evolution over a cosmic timeframe in an unclear reflection on the place that humans occupy in the universe. The movie was almost entirely set in magnificent, interplanetary locations in keeping with such concepts.

Kubrick was an expert at evoking powerful emotions through his use of visual design. He used the perceptions of vastness, futurity, and occasionally startling artificiality to portray emotions ranging from awe to fear. His meticulously created sets and visual effects, as well as the sparse and purposeful use of colours, all served to bring things into perspective. The events of 2001 are set against the immense sweep of the cosmos itself.

Blade Runner

The two Blade Runner films, which were both released 35 years apart, have visually distinct yet remarkably similar aesthetics. Respected filmmakers of the era, known for their distinctive visual aesthetics, are in charge of directing them. Blade Runner is extremely tangible evidence of Ridley Scott and Denis Villeneuve’s rigorous working methods and their ability to engender a type of fascination, an immediate immersiveness in their sights. In the dystopian universe of Blade Runner, technology that appear to make life easier come at a steep existential cost.

With its packed streets and abundance of neon lights, the visual world-building of Blade Runner convincingly captures this impression of social disintegration coexisting with modern technology. When scenes take place in isolated, self-contained worlds that amplify their emotional contents, such as when Harrison Ford’s Deckard hears the villain’s penultimate monologue or when Ryan Gosling’s Officer K is put through the Voight-Kampff test, both films, which combine elements of cyberpunk and film noir, heavily employ shadow and moody lighting.

Enter the Void

Gaspar Noé, a contentious filmmaker, is the author of the extremely experimental art film Into the Void. The main characteristic of this picture is psychedelic, and it draws its inspiration from a trip to a mushroom farm when the director was a teenager. While Enter the Void lacks a coherent storyline, it does have a clear context that can be tracked in the lives of the two siblings who play the movie’s central characters. Yet once the protagonist Oscar is shot in a club, the majority of the film is devoted to a fanciful afterlife experience.

Every moment in the film is presented in a visceral, voyeuristic way by Noé, who also overwhelms the audience with an intensive barrage of strobe lighting, vibrant colours, and immersive sound design. The uncompromising quality of Oscar’s soul wandering over his family’s history and present events may offend viewers, but they cannot dispute the strange nature of the film.

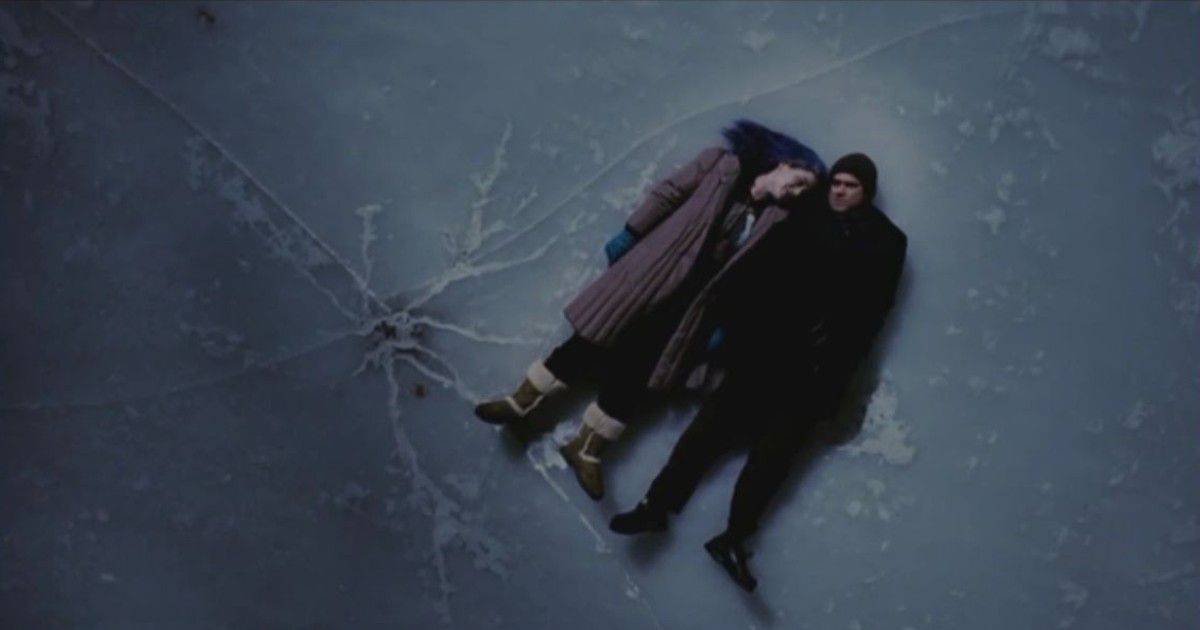

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

One of those films, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, has melancholy in every scene and frame. The film portrays emptiness and longing while stirring up memories of happier times. It is full of chilly colours that contrast with brilliant colours of red and blue. The protagonist goes through a memory-removal procedure to erase all memories of his ex-girlfriend after a traumatic breakup.

The majority of the film is set in the character’s mind as he interacts with his most treasured romantic experiences as they are gradually erased from his memory. In order to convey grief, passion, and the central character’s disorienting uncertainty with equal force, director Michel Gondry uses a variety of practical effects, striking natural backgrounds, and a strong colour language.

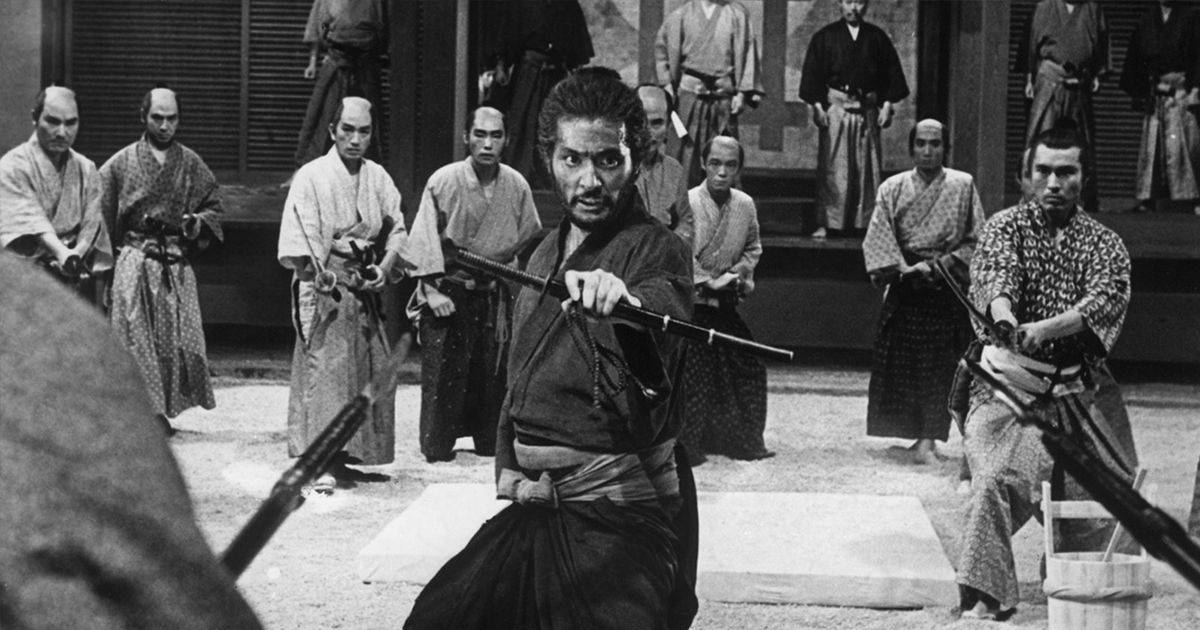

Harakiri

A ronin, or masterless samurai, visits the palace of a samurai clan and requests to perform ritual suicide, or seppuku, in Harakiri, one of the most significant samurai films ever made. The 1962 film is still highly regarded for its captivating story, in which the main character progressively exposes the prestigious clan’s duplicity by using their own rules of honour.

The exceedingly plodding film Harakiri takes place almost exclusively in one place. Despite this, the film’s expert use of camera movements and visual arrangement engages and stimulates viewers. With its arresting visual compositions, this black-and-white film captivated viewers. Its very planned camera movements, such as carefully placed long takes, slow zooms, and dramatic yet aesthetically pleasing movements during its conflicts, helped to heighten the suspense and drama.

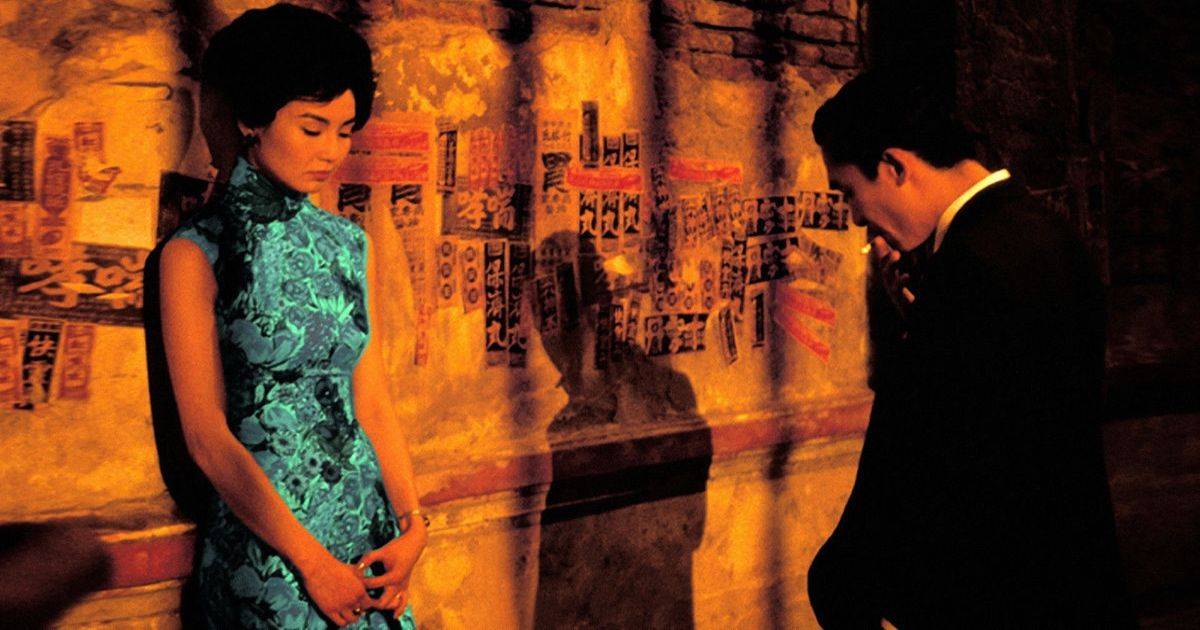

In the Mood for Love

Wong Kar-wai, a director from Hong Kong, is regarded as an auteur and an expert at creating atmosphere. While Wong is known for this ability to evoke a unique set of feelings with each film’s atmosphere, In the Mood for Love is usually regarded as his pinnacle work. In the film, two people who were never meant to be together fall in love and seek solace in one another while attempting to maintain their own moral boundaries.

With these two individuals, Wong Kar-wai uses the mise en scene to create a passionate bubble cosmos. This is most obviously done through the use of warm, rich hues that have a dreamlike feel. The emotional high points of the film, however, occur when this secret world of theirs collides with their outside reality. To convey want and longing, the movie makes use of the claustrophobic settings of 1960s Hong Kong, slow-motion effects, and extraordinarily expressive blocking.

Lost in Translation

Lost in Translation, a film starring Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson as two strangers who experience an odd, transitory connection, is warmly recalled as a unique take on the concept of romance. The mise en scene, which has a very evocative tone and sets the atmosphere for the central characters’ emotional problems, is an essential component of how this film delivers its point. The setting of Lost in Translation is Tokyo, where the characters played by Murray and Johansson are both dealing with severe existential crises. Their ongoing loneliness and incapacity to interact with their surroundings worsen their moods. They eventually develop a bond with one another along the route, which brings comfort and familiarity.

From the disorientation caused by Tokyo’s neon-colored streets to the sensitive emotional tone produced by the numerous images of the night sky, the film’s ambient visual style reflects this transition at every turn. The movie is in a perpetually vulnerable position to examine the emotional states of the people because of the contrast between the visual activity of a strange society and the seclusion of the several places set in the chilly, de-saturated evenings.

The Godfather

The Godfather is regarded as a classic for countless reasons, all of which may be roughly summed up as an unbreakable cohesiveness between every component of its mise en scene. In order to capture the authentic essence of New York in the 1940s and the Italian-American ethnic culture, director Francis Ford Coppola made the film in this way. Using slow, deliberate camera work that subtly transmitted suspense and expectation, dark, brooding lighting that changed with the characters, and other techniques, he built his drama upon this foundation. The main reason the film is still admired by everyone is due to the way its mise en scene speaks volumes and tells his story in an elegant, complex manner that has never been surpassed.

The Shining

It is the best and most well-known creation of a director skilled in the most intricate spheres of dread and wonder. The Shining is Stanley Kubrick’s most elegant and pure expression of his preoccupation with the fear of rigid geometric arrangements. There are several reasons why The Shining has endured as a classic work of horror, including a location painted in the ominous colours of red, endless loops of labyrinthine hallways, and iconic camera angles. The main cast of this film, which is set in a secluded hotel in the snowy highlands, consists of just three individuals, but the hotel itself serves as the genuine enemy. That was pure genius on Kubrick’s part to be able to depict such an idea in such a clear-cut, cunning way.

Throne of Blood

Maybe the most well-known Japanese film pioneer and master of enormous cinematic spectacle is Akira Kurosawa. His adaptation of the well-known Macbeth, Throne of Blood, starred Toshiro Mifune in the role of Shakespeare’s titular hero. Despite being in black and white, Kurosawa’s theatrical imagination was on full display in this film, which laid out its ideas in a haunting mise en scene that was full of mystery and shadows. Every frame of Throne of Blood is ablaze with a sinister presence, whether it’s from the ominous camera angles, the palpable stream of greed and passion communicated in Mifune’s screen placements, or the abundant use of fog and contrast to suggest impending doom. Throne of Blood is frankly devoid of any frame that could be called boring or conventional.

Tokyo Story

One of the most influential directors in cinematic history, Yasujiro Ozu, is widely regarded as having produced his best work with Tokyo Story. Ozu is recognised for his straightforward, realistic approach to filmmaking, which he developed over the course of his career and was viewed by some as a radical departure from the Hollywood-dominant standards. The best example of this was in Tokyo Story. The film depicted the universal story of an elderly couple struggling to integrate into the lives of their adult children.

But it’s amazing to see how Ozu’s unique cinematic eyes capture their quiet struggle. Ozu was known for abstaining from all camera movement, and Tokyo Story does not. Instead, it methodically depicts the human drama with low-angle shots, and the movie’s themes emerge gradually over the course of numerous challenging and frequently subtle subtleties in regular family interactions.

Being a binge-watcher himself, finding Content to write about comes naturally to Divesh. From Anime to Trending Netflix Series and Celebrity News, he covers every detail and always find the right sources for his research.